Trying It On, Royal Court

Wednesday 24th October 2018

Playwright David Edgar is lucky. To begin with, he appreciates his good fortune in having been born in 1948, which means that he was 20 years old in 1968, the year of student revolts and popular uprisings worldwide. Like the poet William Wordsworth, he felt that “Bliss it was in that dawn to be alive, but to be young was very heaven.” At the same time, he has been, like many other student radicals, acutely conscious of the problems of squaring political convictions with artistic ambition, and especially aware of how many 68ers and other leftists made the journey into right-wing convictions by the early 1980s, becoming cheer leaders for Ronald Reagan in the States and Margaret Thatcher in Britain. So his latest one-man play, which he performs himself, is a conversation between the person he is now at age 70 and his younger self.

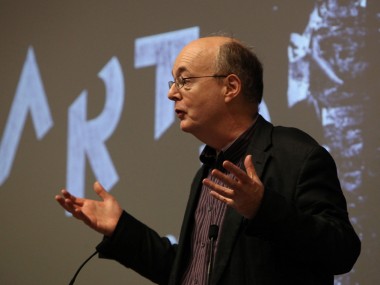

With a very English self-deprecation, Edgar begins this 85-minute show by pointing out that although this might be called a “play”, the “actor” hasn’t learnt his lines, hasn’t actually acted since he played Captain Bligh in Mutiny on the Bounty at university, and that he intends to ask the audience “challenging and potentially revealing questions”. It soon becomes evident that, indeed, Edgar does not intend to act, but instead will read much of his text from an autocue at the back of this studio theatre and tell his autobiography in his own way, which includes snippets of interviews with friends from the past and a small assortment of other radicals from the late 1960s and early 1970s. The show charts the history of the British left and a recurrent theme is the danger from right-wing populism.

Early on, Edgar asks for a show of hands: how many of us voted the same way as our parents, have we ever voted Conservative and who voted for Brexit? I’m happy to answer these questions, but — as he predicted — this kind of exercise can be uncomfortable. The woman sitting next to me has voted Tory, and had also voted for Brexit. I instinctively inch away from her. As Edgar suggests that the gains of the “Sergeant Pepper generation” are now going to be reversed, he begins his time-traveling monologue. Soon we’re deep in his experiences at Manchester University, with student attempts to abolish the exam system, and a minor occupation and plenty of familiar leftist rhetoric. Mindful of his chosen title, he asks whether self-portraiture is a way of trying it on, and if so what is the “it”? And then he literally tries on a Black Power glove, before giving a tentative revolutionary salute.

But the next stage of this personal history is perhaps the most interesting. Edgar moves to Bradford, where he becomes the writer for the General Will, a small agit-prop company, performing Marxist plays to working-class audiences. He vividly conveys the surreal joys of community arts activism and then some of the changes that affected left-wing groups in the 1970s, when identity politics — feminist, gay and black — came into conflict with Marxist ideologies. As the new practices of personal politics arrived, he explains how straight male lefties saw them as a “distraction” from the main anti-capitalist struggle. To add density to the story, he includes video interviews with comrades from the past, and the voices of feminist activists come across loud and clear.

As Edgar leaves Bradford, and begins to enjoy success — writing Destiny (1976) and Maydays (1983) for the RSC — he finds himself in the paradoxical situation of so many middle-class radicals. The object of his desire for social change, the working class, is nowhere to be seen; his main instrument of intervention is the pen, not the molotov. Yet he finds he can do more by writing for Marxism Today than by marching, by writing about Eastern Europe than by striking, and the most by improving the condition of playwrights and theatre workers. As well as applauding the thousands of small, practical, often legal, improvements in people’s lives, instead of striving for utopian fantasies.

All this vast sweep of history is so dazzling it almost defies disagreement: there are so many voices, so much detail, some very familiar to anyone who was part of the British left, some very particular. It’s hard to fault most of the analysis, although I would point out that not every student who went to university in the late 1960s was a radical and that loose talk about generations hides as much as it reveals. Of course, a majority of people over 65 voted for Brexit, but then the Babyboomer generation was never a phalanx: it included many more traditionally minded straight people than young radicals. After all, in the late 1960s, only about 7 per cent of the population went to university.

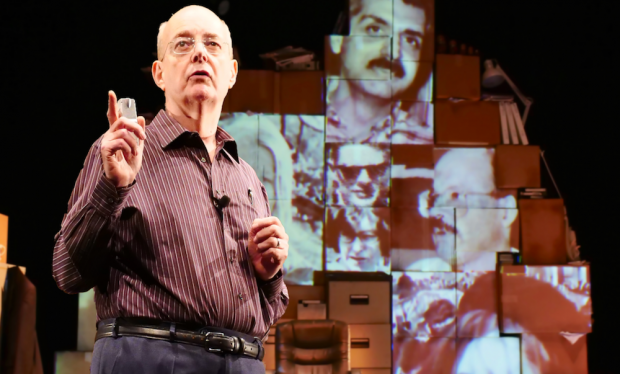

As a performer, Edgar speaks clearly and softly, with an attractive, warm self-ironizing charm. He has been well served by director Christopher Haydon, designer Frankie Bradshaw and stage manager Danielle Phillips, who have created a set that, with its cardboard boxes and filing cabinets and orthopedic chair evokes the playwright’s studio. Various props, from red balloons to a bucket, from old magazines and card placards to leaflets and angle-poise lamps, give him plenty of room to illustrate his ideas in a gently amusing way. Projections of interviews and other visual aids give the show a vibrancy and add to its humanity. Although Edgar could have said more about what it really feels like to look back at his younger self, Trying It On is appealing in its intelligent articulation of personal uncertainties and political doubts.

At times very funny, often instructive, this trip down memory lane includes an amazing twist near the end that I simply didn’t see coming, and that manages to subvert the single viewpoint inherent in the monologue form. This surprise brilliantly reminds us that every generation faces similar problems of reconciling the desire for change with a sense of reality. As Marx once said, “Men (okay people) make their own history, but they do not make it as they please; they do not make it under self-selected circumstances, but under circumstances existing already, given and transmitted from the past.” This show could have no better epigraph.

This review first appeared on The Theatre Times