Ugly Lies the Bone, National Theatre

Thursday 2nd March 2017

Theatre increasingly uses digital delights to enhance audience enjoyment. And you can easily see why. Visual effects that mimic the experience of plunging into virtual reality inject a much-needed wow factor into otherwise quite mundane stories. And if there are plenty of British companies who use such effects, currently it’s American playwrights, such as Jennifer Haley, who are leading the way in the art of the eye-popping visual. The latest arrival — at the National Theatre — is Lindsey Ferrentino’s play, Ugly Lies the Bone, which was first staged in New York a couple of years ago and now marks her London debut.

Its subject is the therapeutic medical use of the world of virtual reality. In experiments, apparently some 60 percent of patients treated in virtual reality pain relief programmes experience a 30 percent reduction in pain — a better result than morphine. One such is Jess, an Afghanistan War vet, whose body was badly burnt by an IED on her third tour of duty fighting the Taliban. Patched up by various hospitals, she has excruciatingly painful skin grafts and a whole range of physical and — because she is also affected by PTSD — psychological disabilities.

The drama begins when Jess returns to her hometown, Titusville, a small place near Cape Canaveral in Florida. The main local employer is NASA, but now in 2011 the last space shuttle is being launched and there are cutbacks and closures. Unemployment is rising, and Jess is irritated by the banalities of suburban life. In one speech she condemns the way that locals just “wanna talk about — grocery lists”, and the price of petrol, and broccoli. She misses the sense of purpose and the pride of being a soldier, someone who was good at her job.

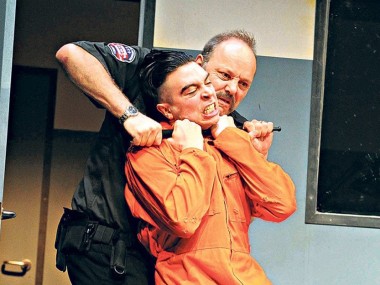

The thirtysomething Jess is less good at domestic relationships. She is uneasy with Kacie, her older sister, and especially suspicious of Kacie’s new boyfriend Kelvin, an unemployed waster. And then there’s Stevie, Jess’s ex, who is now married, and works as a gas station attendant. He is awkward, but oddly friendly. But can he get over the fact that Jess has been so violently disfigured? At first Ferrentino turns up the comedy as Jess, who is in constant agony, is confronted by the obsessive positive-thinking of her closest friends. By making her vet a woman she is also able to crystallize a host of issues about body image, attraction and beauty. The title of play alludes to Albert Einstein’s two-line verse that ends: “Beauty dies and fades away, but ugly holds its own.”

Jess’s therapy requires immersion in a snowbound world of virtual reality, while her offstage therapist leads her through the process of constructing an environment strong enough to distract her body from the feeling of constant pain. Kate Fleetwood delivers a bravura performance as the agonized vet, her stiff puppet-like movements gradually thawing as she learns to appreciate the humanity of those around her. She convincingly communicates the wariness that results from extreme pain, and her anger feels genuine. In one moving moment, she changes into a dress, determined despite the difficulties. It is typical of a thoroughly touching performance. She gets good support from Ralf Little (Stevie), Olivia Darnley (Kacie) and Kris Marshall (Kelvin).

One of the themes of the play is homecoming, and homesickness. After more than a year in a military hospital, Jess wants to come back to her home town. But when she does she feels alienated from those that are nearest and dearest to her. Her slow change in attitude has less to do with her pain-controlling therapy than with surrender to a kind of relentless Florida sunniness that is part of the American Dream. For although Ferrentino is quite critical of contemporary American society, and clearly sympathizes with those communities that have been left behind when major industries move on, she doesn’t give herself the space to develop these bigger ideas.

Indhu Rubasingham’s production fields Luke Halls’s impressive video projections and Es Devlin’s versatile set, which flips from therapy session to domestic everyday scenes with smooth alacrity. The projections are entertaining, without being amazing. But while the 95-minute play is never boring, it is never very profound either, and the ending feels oddly inconclusive. And thin. Ferrentino seems determined to convince us that these are fundamentally nice people, when a bit of real emotional ugliness might have been more dramatic. With the advent of Trump, the decline of local industry and the desire to restore past greatness are hot topics. Although this piece nods in their general direction, it doesn’t quite get to grips with the larger political disfigurement of the USA.

This review first appeared on The Arts Desk