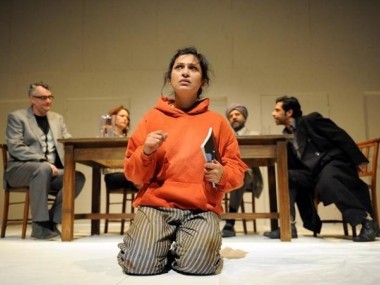

Underneath, Soho Theatre

Friday 25th November 2016

Our culture adores the beautiful, and is fascinated by the ugly. Especially the monstrous. In Pat Kinevane’s third solo play for Fishamble, the Dublin-based new play company, the idea of skin-deep beauty and of the sadness that lies underneath disfigurement are both explored in a monologue performed by the playwright. First produced in December 2014, the show begins in a crumbling tomb that lies apparently abandoned, amid sheets of gold material, on an otherwise more or less empty stage. The darkness heaves with portent, and we strain to see in the half-light.

Then what is this? An arm appears from the tomb, a slab moves away, and a corpse rises from the dead. Wrapped in funeral bandages, like the proverbial Egyptian mummy, and discolored with a black hue that merges seamlessly into the darkness, Kinevane emerges from this crypt. He plays a character that the play text calls Her, and his manly shape serves to emphasize the fact that this is a story about transformation and entrapment in a body not our own. With a blacked up face, crossed by a golden scar, the whites of his eyes and teeth gleaming in the murk, Kinevane sets off on his monologue, first chatting directly with audience, putting us at our ease, making friends, helping us feel relaxed about being in the presence of death.

Then the actor and playwright tells the story of Her. At the age of nine, she is struck by lightning, which not only disfigures her face, but also changes her body into a larger, more masculine kind of femininity. She looks frightful; she suffers fits. People think she is a monster. As a result, she is shunned by almost everyone she meets. A lonely childhood is endured and then, like a ray of sunshine on a rain-soaked day, at the age of 15 she meets Jasper Wade, a super-intelligent, really fit, really rich, cool dude. Amazingly, she hits it off with him, or does she? Kinevane explores this ambiguous relationship with a mixture of tenderness and brutality, while the story lurches towards its tragic conclusion.

Along the way, this production — directed by Jim Culleton, with music by Denis Clohessy and choreography by Emma O’Kane — travels into the depths of ancient Egypt, an adventure inspired by Her mother’s love of Elizabeth Taylor’s Cleopatra. Lots of gold cloth and gold scarves and gold notebooks and gold gloves. Jasper is represented by a golden lampshade. There is even some golden-thread knitting. All very Nefertiti. And, amid the strangeness and the dark there are little flashes of laughter. This show combines screaming agony with raucous jokes.

Using recorded voiceovers, atmospheric music and quick changes of lighting, Kinevane not only tells the pathetic story of Her and her hopes, but also intercuts this with satirical sequences in which he mercilessly mocks reality television and especially shows like A Place in the Sun. He is denouncing our obsession with superficial beauty, and clawing at our interest in celebrity, in impossibly beautiful houses and homes in faraway perfect places. By the time the character Her makes friends with a couple of prostitutes, the little victories that she scores over the bullies and hypocrites she comes across seem to count for much more than their actual worth.

And there are some small victories. As the piece’s title suggests, this is a play about how our real subjective selves lie beneath the veneer and gloss of appearances. Likewise, it argues that those who have the misfortune to look ugly — and the monstrous is just a rhetorical exaggeration of anything that is not attractive to society in general — are as valuable and as interesting as the coolest of the cool. It’s a very simple point to make, but Kinevane makes it strongly and dominates the stage, walking, prowling and dancing his way through the story.

It’s a performance that is both charming and terrifying; when he gets angry, the volume of his howl is enough to shake the walls of this venue’s studio theatre. It certainly frightened me. With his eye-popping make-up and mouldering shroud, he looks imposingly monstrous. Yet he also easily calms down and can raise a smile at the drop of a golden cloth. I even grew to like his singing, although he can get uncomfortably close to you in this tiny studio theatre. But while I feel that everything he has to say about beauty and the person underneath a damaged exterior is true, and just, and occasionally beautiful, he didn’t tell me anything I didn’t already know. Yet if the insights are meagre, there’s no denying the power and the fury of his performance — at times, it almost blew me away.

© Aleks Sierz