Wastwater, Royal Court

Monday 11th April 2011

Airports are non-places; transient, temporary, unhomely, cold. To be in one — especially if it is Heathrow — is usually a bad experience. In the poetic imagination, however, airports can be strange and symbolic spots, the focus of powerful emotional forces. Thus Simon Stephens’s new play, Wastwater, which takes place in three different locations in the vicinity of Heathrow, is a punchy account of human relations in a globalised world.

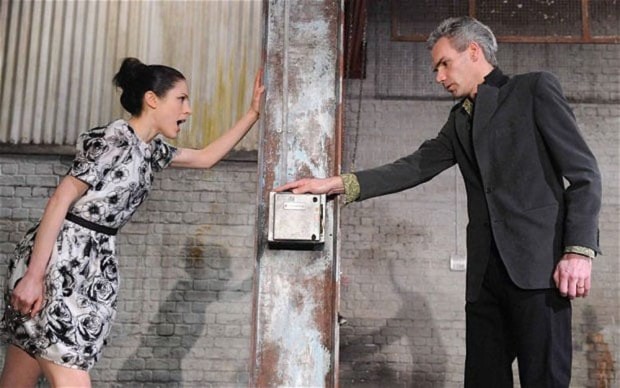

The 100-minute piece is constructed as a triptych, with three separate scenes featuring three different couples, which are all tenuously related in terms of their relationships, yet strongly entwined by theme. In the first scene, set in a greenhouse near Sipson in Middlesex, twentysomething Harry is taking leave of Frieda, his mother. Harry is off to the airport to fly to Vancouver, and Frieda, it soon emerges, is his foster mum. They get on very well, so the parting is awkward, unsettling, sad. You get the feeling that Harry is unlikely to return for a visit — he’s making a new life, a new home, for himself. In scene two, the location is another example of a non-place: an airport hotel room. Here, another two characters — thirtysomething Mark and fortysomething Lisa — are preparing to have sex. They are nervous, edgy, uncertain. Both are married so this is a transgressive and temporary situation. Very unhomely. But are their desires at all compatible? The final scene, which takes place in a cold deserted warehouse, is even more tense than the second one. Fortysomething Jonathan has found a Philippino child on the internet, and has come to illegally adopt her. His contact is Sian, a young woman who delights in scaring the living daylights out of him. And she is an expert in doing that.

Stephens writes tense, edgy dialogue, which nevertheless allows his characters to break off and ponder the wider shores of the world. He takes his title from Wastwater, the deepest lake in Cumbria, and in England, a symbol of the murky depths of the degraded human spirit which not only pollutes the planet with air travel but also stirs up gross imaginings and nightmare fantasies.

In Katie Mitchell’s superb production, every time an airplane passes overhead, a gloomy shadow falls over the scene. Yes, this is a journey into different hearts of darkness: Stephens shows a world where abandoned children rely on foster parents, which they then leave for ever, and where marriages need adultery to survive, and where the childless couple or the paedophile can buy a child on the internet. Lizzie Clachan’s design powerfully evokes the rooted and the unrooted places of our emotional fears.

Each of the scenes is linked, although it would spoil things to reveal exactly how. Certainly, the new digital technologies feature in each scene, whether it is the mobile phone that disrupts conversation or the internet which spreads porn and offers illegal adoption. But there is also some irony in the darkness with repeats of the “Habanera” from Georges Bizet’s Carmen — with its refrain “love is a rebellious bird” — offering an underscore to these tales of uncontrolled desire. Giving this vision of children at risk, and of the destructive potential of new technology, a compelling flavour is Mitchell’s precise and pointed directing. Her actors do some utterly convincing work: Linda Bassett and Tom Sturridge lend a subtle touch of the incestuous to this piece’s mother and son; Jo McInnes and Paul Ready are the unsuitable couple at the centre of the play; Amanda Hale and Angus Wright are the fearsome child trafficker and her sick client.

Metaphoric, allusive, and thoroughly disturbing in its evocation of suspicion and uncertainty, Wastwater is a thought-provoking play whose quiet intensity stays with you for days — its effect is like that of a ugly stone dropped into a pool, which results in constant ripples of dirty water lapping at your subconscious.

© Aleks Sierz