We Know Where You Live, Finborough Theatre

Monday 3rd August 2015

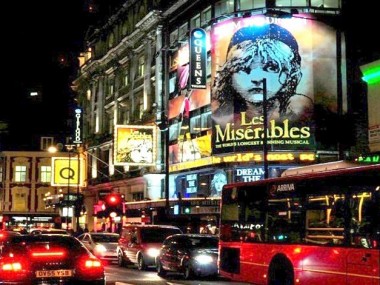

I live in Brixton, south London. As in many parts of the metropolis that were once scorned as ghettos, or dumps, this is now a very desirable borough. So gradually all the signs of urban gentrification have become visible: property renovation, city centre regeneration, farmers markets, pop ups and fairs. Flowers now bloom on window sills. And, as the influx of young middle-class professionals increases, house prices soar. I well remember the day when a local resident told me that a house in the street next to ours was now worth a million puonds. So, when I heard that this new play by Steven Hevey, a playwright on attachment at the Finborough, is about gentrification I immediately wanted to see it. Originally done as a staged reading during this venue’s Vibrant festival of new writing in 2013, We Know Where You Live certainly proves that he can write good dialogue.

The story starts well. An estate agent is showing a twentysomething professional couple — Ben and Asma — around a small flat in a rundown area. He talks the language of the salesman: this location, he claims, is “beyond urban”. It’s a “vibrant hybrid environment”. These synonyms for a poverty-stricken area give the scene a satirical feel. As does the mention of a “cheeky little market” nearby. Never mind, the rent is £1200 a month, and Ben and Asma soon move in.

Part of a new wave of gentrifiers, they soon meet Mary, the leader of the local community association, and two working-class residents who are also volunteers on this body, Keith and Roy. Keith is a member of what, according to the media, is a problematic minority: the white working class. Certainly he is unemployed, resentful and aggressive; he supports West Ham and takes pot shots at foxes with an airgun. Roy is a complete contrast: he is black, used to work for the Council and has been a lifelong union member. Just don’t get him started on the subject of Margaret Thatcher.

But while Mary (and with less enthusiasm Keith and Roy) support the Council in its plan to build a new shopping centre, Ben — who works as an intern for a trendy architect — opposes the plan. When he sees that some old Victorian cottages face demolition to make way for the new development, he campaigns to preserve them. So the battle lines are drawn: the working class members of the local community want progress, modernity and change. The middle-class gentrifiers want heritage and historical conservation. On top of this, Ben and Asma find that their relationship comes under strain as he becomes more earnest in his campaigning and she discovers that he’s not much fun anymore.

Hevey writes in a lively way and his scenes have well-constructed conflicts, as well as buzzing with ideas about identity, city life and capitalism. Other issues include sexual harassment, homophobic abuse and random violence. Not to mention rising house prices and poor career prospects. But he packs such a lot into the 100 minutes of running time that the emotional intensity of the story is a bit too overheated and the play could have been improved with some contrasting, less clamorous scenes. In terms of symbolism, the recurring image of the urban fox — reminiscent of Chris Goode’s Men in the Cities — doesn’t quite work. Worst of all, the final scene feels redundant and awkward.

Still, there is much to enjoy in John Young’s sharply focused production, and the cheerful and committed acting does a lot to alleviate some of the more banal aspects of the situation. Matt Whitchurch and Ritu Arya are well matched as Ben and Asma, while Paddy Navin (Mary), Daniel York (Keith) and Gary Beadle (Roy) are very good as the locals. Ross Hatt plays several smaller roles, including the Estate Agent. This is an occasionally powerful piece from a writer who shows a great deal of promise.

© Aleks Sierz