Widowers’ Houses, Orange Tree Theatre

Friday 9th January 2015

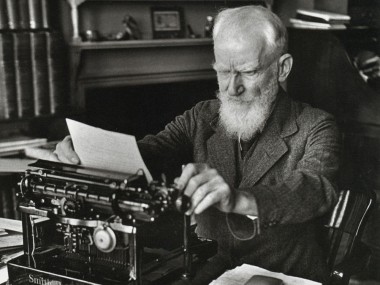

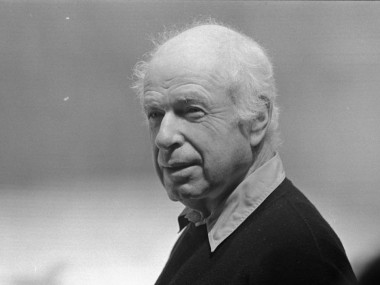

Like every other critic, I have been immensely impressed by Paul Miller’s programming at this venue. Instead of rolling over and dying when the Arts Council (surely a most cretinous organisation) cut his entire grant on the first day of his job as artistic director, he has fought back and shown that his theatre has a distinctive role to play in the robust ecology of London theatre. What’s great is his confident mix of modern classics and cutting-edge contemporary plays. This revival of George Bernard Shaw’s often mentioned (in history books), but rarely seen 1892 play is both charming and thought-provoking.

The first scene is a classic piece of Victoriana. We are on holiday in Remagen on the Rhine with Harry Trench, a young and impoverished doctor, and his friend William Cokane. At their hotel, they meet fellow Brits in the shape of Sartorius, a self-made successful businessman, and his beautiful if outspoken daughter Blanche. True to the conventions of late-nineteenth-century drama, Harry and Blanche have a couple of charming conversations, then rapidly fall in love and become engaged. So far so sweet. But when everyone is back in London, the climate changes from sunny to overcast. The main cloud that appears concerns Sartorius, who is a slum landlord and who quarrels with Lickcheese, his chief rent collector, accusing his employee of being too soft on the tenants.

When Harry visits, he gets drawn into this argument. Being young and idealistic, he says that he abhors the making of money from other people’s misery, and defends the rights of poor tenants. More than that, he insists that his fiancée Blanche should refuse to accept any of her father’s tainted money when they marry. No, they will live on his own meagre income. So far so idealistic. But Shaw is too intelligent a dramatist to leave things so clear, and he begins to twist the situation by revealing that Harry also depends on money derived from mortgaged slum tenements and is thus as culpable as Sartorius. If both young and old are dependent on the dirty money of crushing exploitation, then who in audience is innocent? Aren’t we all nice middle-class people comfortable because of untold human misery? You can see why Shaw included this his first play in his volume called Plays Unpleasant: it was intended to seduce the audience with romantic entertainment, then wallop them with his socialist message.

For me, this part of the play is more successful than the romantic strand. The hotheaded Blanche and the naive Harry quarrel passionately, and then reconcile in what feels like a very unconvincing piece of writing, as if Shaw couldn’t quite push his own insights to their logical conclusion. He wallops the audience with his social criticism and then lets them off the hook by appealing to their modern notions of romance. Still, I am grateful that Miller has given us the opportunity to see the way that naturalism and melodrama are held in uneasy embrace in his well-paced reading of the play.

Miller also coaxes solid performances from his cast: Alex Waldman and Rebecca Collingwood make an appealing young couple, while Patrick Drury is a cool and charming capitalist. Colourblind casting means that Stefan Adegbola can play William, often as a refugee from an Oscar Wilde story, and Simon Gregor’s Lickcheese is barnstorming and battle-scarred. Finally, Lotti Maddox is a spirited parlour maid. Although some of the acting is occasionally uneven, it is the ideas of the piece that stay with you. Shaw shows not only that slum landlords have no conscience, but also that people can soon abandon their ideals when it is expedient to do so. His criticism of Sartorius is wide ranging and sucks in the whole capitalist system. Whatever the relevance today of this kind of socialist criticism, this drama is more interesting as an example of an early work than as a full-fledged masterpiece. When I heard that Shaw once described this play as “one of my worst” I thought he was being typically ironic, but now that I’ve seen it I can take his point literally.

© Aleks Sierz