Wolves on Road, Bush Theatre

Thursday 14th November 2024

Cryptocurrency is like the myth of El Dorado — a promised land made of fool’s gold. Despite its liberatory potential, it frequently attracts sharks or, as the title of Beru Tessema’s new play indicates, hungry wolves that gobble up defenceless sheep. After the success at this venue of his 2022 play, House of Ife, the playwright returns to the Bush Theatre with a subject which is original and a cast which includes a cameo by Jamael Westman, star of the original West End production of Hamilton. This time, however, some slack plotting and predictable consequences undermine the drama of a slightly toothless, even limping, Wolves on Road.

The story, set in East London in 2021, starts promisingly enough with Manny, a 21-year-old mixed-heritage Londoner living with Fevan, his Ethiopian-British mother, who works as a chef and dreams of opening an “Afropean fusion” restaurant. Manny is selling designer handbags on Instagram, but runs into debt when their dodgy provenance causes customers to fall away. Desperate for cash, and living in the shadow of Canary Wharf’s beckoning high rises, he asks his best mate, the Somali-British Abdul, for help. Abdul introduces him to the rollercoaster world of cryptocurrency. For a while things go well, then Tessema ups the ante.

Both Manny and Abdul get involved with a company called DGX, which offers them bonuses if they can sign up local people to invest in a bitcoin scheme that will provide financial rewards as well as acting like a mutual credit union. Run in their area by the charismatic entrepreneur Devlin (Westman), the scheme sucks in not only Fevan, but also her boyfriend Markos, an Ethiopian migrant who drives buses and works for Uber in his spare time. Their project of saving money to invest in a restaurant at first gets a boost from investing in DGX, but there is surely no prize for guessing how this scheme will turn out.

Tessema’s dialogue, especially from the mouths of Manny and Abdul, sizzles with demotic energy, and the sparks from their use of slang and pop culture references light up the theatre. But the playwright is not just a bright wordsmith — he’s also a fine creator of character. Apart from the mouthy youngsters, by now quite familiar figures on British stages, he gives us Fevan and Markos, who are aspirational and hardworking. The scenes in which the older man — who is trying hard to help his own son reach the UK from Libya — clashes with his lover’s son Manny are particularly strong in terms of emotional truth.

But, sadly, this is not enough. The problem is the plotting: it is pedestrian and lacks any interesting twists. Worse still, the second half of the evening begins with a lecture, delivered by Devlin, about cryptocurrency and mutual credit unions, which while being interesting in content is pretty static in terms of theatre. Not even Westman’s considerable charm, and appealing personality, which he uses for some great audience interaction, can save this scene from being a dramaturgical grind. From then on, the plotting is a plod.

As the action reaches its predictable conclusion, it is also disturbing to see that the playwright’s view of the black community scarcely changes: like Manny in the opening scene, the black community of all ages is shown to be credulous, naïve and greedy. Not very nice. Only the character of Fevan is wise enough to question the notion of putting all your trust in crypto. So despite the articulation of the idealistic vision of mutual credit unions for black people, which contest the hegemony of white folk over the financial system, a legacy of colonial exploitation, the result of the story is inevitable disappointment for all involved in crypto speculation.

Some of the ideas of the play are repetitive, and there is something unconvincing, and even insulting, in its overall idea of ignorant and gullible black people. So while there are some lovely moments of playwriting, which include the biblical quotation about the love of money being at the root of evil, the play’s plotting creates a sense of depressing sadness. And yet. There is so much potential here: I would love to see how Fevan’s story played out in the long run, and Markos and his son deserve a play all for themselves. Oh well, perhaps another time.

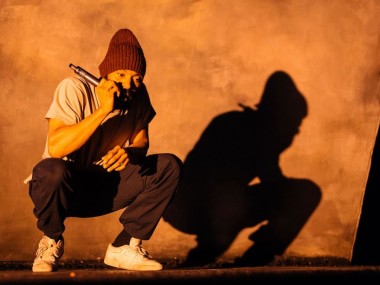

In a co-production with Tamasha, Daniel Bailey’s production features a versatile set by designer Amelia Jane Hankin, with Gino Ricardo Green’s video work and Duramaney Kamara’s sound a real treat. As well as the absolutely riz Westman (catch him before he leaves the cast after 23 November), the young ones – Kieran Taylor-Ford (Manny) and Hassan Najib (Abdul) – have an exciting stage presence. By contrast, Alma Eno’s Fevan and Ery Nzaramba’s Markos are more grounded emotionally. But despite the pleasures of some of the writing, the strength of the family conflicts, and the originality of its central theme, this is a deflating evening.

This review first appeared on The Arts Desk