You Stupid Darkness!, Southwark Playhouse

Monday 20th January 2020

Turn on the news. Go on. No? Okay, switch on the radio. Why not? Oh, I see, because the news is always bad. Yeah, I know what you mean. All those stories about how we’re doomed because of global warming and ecological disaster, about how capitalism is on its last knees because of the financial crash, and all the rest of these terrible things. Yeah, it’s depressing; it’s a world of despair; it’s a valley of tears. I get it. All true, but how about we do something about it? Help people. You know, like the Samaritans do. This is the premiss of playwright Sam Steiner’s latest show, which opened at the Drum, Plymouth, about a year ago, and is now at the Southwark Playhouse with a slightly different cast.

A co-production between new writing company Paines Plough and Theatre Royal Plymouth, You Stupid Darkness! is set in a kind of 1980s-style office which runs Brightline, a helpline to aid people to cope with what sounds like a wide-ranging catastrophe (global warming has already created massive disruption and emergency — sirens wail constantly in the background). As usual with a play set in the workplace, Steiner quickly introduces us to his four different characters. The office is led by Frances, a bright, relentlessly feelgood person who is also heavily pregnant, and to her co-workers, who are all volunteers working one night a week at Brightline: Jon, an insurance pen-pusher, Angie, a kooky mix of provocation and fragility, and the new boy, 17-year-old Joey, who is still at school and doing work experience.

This format, which enables Steiner to acquaint the newcomer (Joey) with the rest of the staff, is a classic of traditional play exposition, and up to a point it works. Through his young eyes we see how these part-time volunteers answer calls from desperate people, how they are trained not to reveal too much about themselves and how they have to be patient — even with the oddballs and the big mouths that phone for disagreeable, sometimes despicable, reasons. All of the characters soon spring into focus: the pregnant Frances, who has a needy partner, is the mother figure, and in fact she treats Joey like a surrogate son; he, in turn, at first calls her “Miss” as if she’s his school teacher; Jon, who is having issues with his partner Andy, is also trying to learn to play the trombone; and Angie is talkative, talkative, talkative. And has a lovely dog.

The problem with work plays like this one is that work is repetitive, and usually based in one place. Having put his characters into this office, Steiner is rather stuck with them doing the same thing over and over again. Basically, they chat a bit about banal things, and answer phone calls. It’s a call center and the phones keep ringing. But one phone call from a desperate person is much like another so the play, which runs for two and a half hours, soon gets bogged down in repetition. Even the device of having two or three characters answering phones at the same time, which creates a cacophony of words, soon gets boring (all three conversations are equally indecipherable). Also, another problem is that Steiner has invented a scenario, but not really found a story. The play has a situation, and some comedy, but no real drama.

Which is odd, given that the outside world has been imaged by the playwright as one of those Caryl Churchill-like catastrophes: the volunteers arrive in gas masks, bridges across the Thames are falling down, mould is choking buildings and the lights keep going out. By the end, gales, snow and rain take their toll: water pours through the office. But the central message suggested by the show is: don’t panic. Even when things get intolerable in the world you can always get by with humour and with a helping hand. There is something very British in this picture of a stoical and amused attitude to complete economic, political and social collapse. Yes, this surely is us.

There is likewise a feeling of general compassion in the idea of these volunteers, who are trained to smile and be positive in the face of tragedy, and there is a throb of generosity in the writing. At the same time, Steiner clearly loves language so he gives us plenty of examples of word play: one character relishes words like “peeve”; another forms the verb “to carpent” from carpentry; then there’s some lisping of the word “vicious” and a satisfyingly sibilant “Sally”. This is matched by some short passages of fine writing: Angie’s wonder at how a box of tissues works and her strained use of a tongue-twister to help with a suicidal caller not only get our attention, but also reveal her character. Finally, Jon’s first name sets up a lovely joke when his surname is eventually given. Nice stuff.

Yet it is also a pity that this play is so overlong and so self-indulgent because its central idea — that selfless volunteers and social workers are in some respects as needy as their clients — is potentially a very rich and politically provocative insight. Sadly, here this remains largely unexplored. While there is a sense of camaraderie among the characters, their relationships never grab us. At some points, there is hope of more drama, as when Frances is asked why she got pregnant, but then the moment passes and nothing is resolved. Similarly you never really get to know why the callers are contacting this helpline, and what they get out of it. During a satirical passage about customer feedback some of them are asked this question — and they promptly hang up.

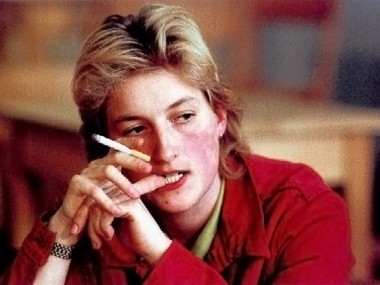

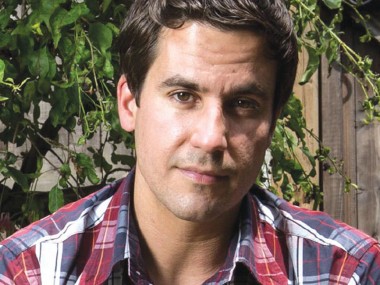

Directed by James Grieve and designed by Amy Jane Cook, whose shabby office features a whiteboard with an encouraging “word of the week”, as well as electrical burn marks and other evidence of urban degradation, You Stupid Darkness! is a very slow show that never really catches fire. Still, the four performers tackle their roles with integrity and commitment: Jenni Maitland’s Frances is exhausting in her bright optimism, Andy Rush is energetic as Jon, Lydia Larson’s Angie is both delicate and manic, and Andrew Finnigan’s Joey is suitably gawky and uncertain. But annoyance at some clunky writing — surely the title of the piece (which comes from a Peanuts cartoon) shouldn’t have to be explicitly explained — and the failure to find a compelling story, is the evening’s chief takeaway.

This review first appeared on The Theatre Times