All We Need Is Music, Sweet Music (Sweet Music)

Thursday 1st October 2020

Prelude

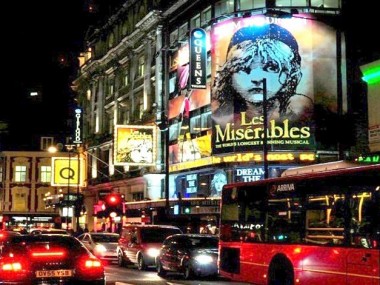

Fantasy is a vital part of all art. In Tim Crouch’s experimental play, The Author (Royal Court, 2009), the actress Esther tells a story about “the day the theatre marched against the war!” Organized by Equity, the actors union, this event was a public demonstration on the “anniversary of the war starting. We were encouraged to go in bits of costume or make-up. Can you imagine! The cast of Mamma Mia, Lord of the Rings, Spamalot, Les Mis, Hairspray, The History Boys, Wicked, Stomp, Joseph, The Lion King! All those actors! […] singing their songs and dancing.” Her verdict: “We were having fun!” It is a moment of utopian revolt when the casts of the entire commercial West End theatre turn out to oppose government policy. Needless to say, this is a fantasy — it never happened. But the image that this brief account leaves in the mind is one of sheer fun in opposition.

In discussions of the West End, this sense of pleasure is key. One could say that there are few things more subversive that the sight of people simply enjoying themselves: pleasure, the atmosphere of enjoyment, can be as political as any orator’s harangue or noisy demonstration. So the pleasure that people derive from commercial theatre is perhaps more than just soporific contentment; maybe it’s the pleasure of human beings who have opened their hearts to their better natures. When an audience is rapt in its attention to music, when people are convulsed with laughter during a comedy, when spectators are busy spectating, whether what they watching is a straight murder mystery, a ghost story or a lavish musical, these people are harmless — they cannot, to use a phrase of Kenneth Tynan’s about Look Back in Anger, be recruited to whip Cypriot schoolboys or be made to lynch black people. Pleasure is subversive because it distracts people from atavistic hatreds and discourages them from following the lead of demagogues. When you leave a performance of Carmen, your first instinct is not to shoot Spanish soldiers; when you enjoy Evita, you don’t immediately plot a coup d’état; after Priscilla Queen of the Desert, you might be inspired to change your wardrobe, but I doubt that you’d be provoked into queer bashing. Yet, in terms of how we look at the politics of commercial theatre, pleasure is not enough.

Act One: how we talk about musicals

When critics talk about musicals in London, what are they usually saying? Well, the answer for the most part is simple: we enjoy articulating our prejudices. Indeed, for some 50 or more years, West End commercial musicals have had something of an image problem. Because they are fun to experience, they are often dismissed as artistically inferior; because they are very popular, they are often seen as aesthetic follies. Indeed, critics rub their hands in glee when a musical flops: people who would be shocked to be seen ghoulishly attracted to the site of a train-crash have no such inhibitions when savouring the car-crash that is the sight of a musical going belly up. Ah, the sweet smell of disaster: how we love to hear news of money lost by commercial companies (although few people celebrate the jobs lost by the actors, singers and production crew — that would be too much). But even success is not enough to win the hearts and minds of most critics. Andrew Lloyd Webber is one of the most hated people in Britain, by the media-making classes, and the reason is not that he is responsible for treating his workers badly, it is because he is successful. This contempt is just another example of a little Englander suspicion of success.

And, by success, I do mean success. Ever since he arrived with musicals such as Joseph and the Amazing Technicolor Dreamcoat (1968-72), Jesus Christ Superstar (1972) and Evita (1978), Lloyd Webber not only saved the genre of the musical in Britain, but he also saved the great theatre buildings of the West End. When, in the 1980s, he went spectacular, with Cats (1981), Starlight Express (1984) and The Phantom of the Opera (1986), his commercial success was phenomenal. In 1991, he made theatre history with six shows running at the same time in London’s West End. In 1994, he repeated his achievement by having three musicals running in London and three in New York at the same time. This is one area in which theatre box office can compete with other mass media such as cinema. James Cameron’s 1997 filmTitanic was once the largest grossing film of all time, making some $1.8 billion; Avatar, James Cameron’s other largest grossing film of all time, made $2 billion. In comparison, The Phantom of the Opera has already made more than $5 billion worldwide, and is still making money. Every single day. The show has been seen in 149 cities in 25 countries, and has played to more than 100 million people. Arguably, The Phantom of the Opera is the highest-grossing entertainment event of all time. Shakespeare, eat your heart out.

But success never equates with artistic merit. If it did, how much simpler things would be. You would be able to align box office success with aesthetic brilliance. In the West End, Agatha Christie’s The Mousetrap, which has been running continuously since 1952 and will probably go on for ever, would be the best straight drama by far. Lloyd Webber would be better than Stephen Sondheim. But because this kind of equation is not convincing, the question arises: why do people enjoy art’s equivalent of fast food? (But that’s a subject for another article.)

Of course, not every musical is the same. Some musical long runners are now almost cultural institutions in their own right. Despite his reputation as a Prince of Darkness, Lloyd Webber’s The Phantom of the Opera is not the longest running musical in the West End. No, that honour belongs to Claude-Michel Schönberg and Alain Boublil’s Les Miserables (opened 8 October 1985, while Phantom of the Opera premiered on 9 October 1986). While I think that there is an aesthetic argument for this musical and several others in the West End at the moment, other musicals are less impressive, especially juke-box musicals such as We Will Rock You. Despite this, musicals have been good news for the West End: they have saved the huge theatres of the Georgian and Victorian London from becoming museum pieces, they have employed thousands of theatre workers, they have encouraged tourism, they have given coachloads of people a reason to visit their metropolis, they have restored a sense of wonder in the theatre.

Act Two: how we talk about straight dramas

If musicals, despite their success, have a poor image, straight drama can — according to the critics — do no wrong. But it is a rare bird. Whenever it is glimpsed in the West End, the straight play is treated like an animal in danger of extinction. It is a victim, driven out of the West End by the mighty power of the musicals, and thus its victim status guarantees its artistic integrity. Just because it has no songs, no tunes and no orchestra, a straight play immediately seems virtuous. Just because there are so few new plays staged by commercial managements in the West End, each one immediately seems like a newsworthy event. Its rarity value guarantees its aesthetic credentials. Critics hug themselves when a new play appears in the West End. Clearly, this is not a recent phenomenon: for the quarter of a century at least, the straight drama in the West End has been in crisis. In fact, it has been in crisis so long that it is now its normal state. This permanent state of crisis is, you could even say, an example of the British discourse of national decline.

So it might be worth reminding ourselves that this was not always so. Up to the mid-1980s, London’s commercial West End was the home for a string of mainstream playwrights. The names Alan Ayckbourn, Tom Stoppard, Alan Bennett, Michael Frayn, Simon Gray and Peter Nichols were often seen in lights. They wrote crowd-pleasing well-made plays that were indeed well-made and did, mostly, please the crowds. But, ten years later, by the mid-1990s, look at the West End and a different picture emerges. Successful plays such as Mark Ravenhill’s Shopping and Fucking or Conor McPherson’s The Weir now dominate the scene — the most typical West End play has now been developed in the public sector, usually at the National Theatre or the Royal Court, occasionally at an out-of-town venue, always using state subsidy. Then, in partnership with a commercial management, the play transfers to the West End, making money for both public and private backers. So normal is this system that when, in the middle of the past decade, Nicholas Hytner, the artistic director of the National, decided to buck the system with his production of Alan Bennett’s The History Boys, some eyebrows were raised. Instead of immediately transferring the play to the West End after its initial successful run at the National, Hytner kept it in the repertoire for much longer than normal, drawing as much money as he could out of audiences, before finally releasing the play on tour to New York and the West End.

Act Three: how we talk about politics

Politics should start with the facts. And, in the West End, the facts are really simple. Last week (October 2010), I counted no fewer than 22 musicals on the West End stages. As against this, there were about 10 straight plays, most of these being transfers from the subsidized sector, plus long-running classics such as The Mousetrap and The Woman in Black. There is also The 39 Steps (a relative newcomer as it has only been running for five years). The only other commercial play was Ira Levin’s Deathtrap, a revival of a 1978 thriller with a couple of star actors (Simon Russell Beale and Jonathan Groff). The one anomaly in this pattern is a theatre which, although not strictly situated in the very centre of Theatreland, is a West End venue which is both commercial and devoted to straight drama, new plays as well as revivals: the Old Vic (although this relies on Kevin Spacey’s private fortune to sustain it).

The changes to the London theatre system that I have been describing are all the result of one event that we can date very precisely: 3 May 1979, the date of Margaret Thatcher’s first election victory. As a result of the policies of her governments throughout the 1980s, British theatre changed profoundly. In the past, it was split into two camps, the commercial and the subsidized, with another little area developing after 1968, which was the alternative theatre and the fringe. By the 1990s, the bracing winds of commerce had blown through the entire British theatre system, and everything had changed. Instead of a balance between commercial straight plays and state-subsidized straight plays, all new drama was now sponsored by state-funded institutions. So whereas once playwrights such as Alan Bennett and Michael Frayn were often managed by commercial bodies, they now all took shelter in the public institutions such as the National Theatre. Newer playwrights such as Lee Hall and Tim Firth (what I would call New Writing Lite) are now mainly produced by the state-subsidized sector.

It was not always like this: two of the most important plays of the entire 20th-century repertoire, namely Samuel Beckett’s Waiting for Godot and Harold Pinter’s The Birthday Party, were produced by commercial managements. Commercial productions sustained play after play by such British playwriting stalwarts as Noël Coward and Terence Rattigan. In the 1960s, the West End had a healthy annual crop of commercial openings.

In the past few years, the West End has enjoyed a boom. In the UK, politics are now almost always conducted by talking about economics, so what are the economics of the West End? Well, “Despite the continuing world economic crisis, with companies failing, bank bailouts and the Pound falling to 1.37 against the Dollar,” says the latest report of The Society of London Theatre, “business throughout 2009 was consistently up on the previous year, particularly so during the third quarter. So far, London theatre seems to have fared better than could have been hoped for, given the severity of the world economic decline.” Booking for major musicals, often imports from Broadway, “continued throughout the year at a historically unprecedented level”. The big driver behind the business in 2009 was star actors in plays, such as Jude Law, Kim Cattrall, Ian McKellen, Patrick Stewart etc. In a record-breaking year, 2009 saw box office takings increase by 7.6%, to almost £505m, the first time it was more than half a billion pounds. “Whilst our musicals continue to flourish, 2009 was an outstanding year for plays — proving that audiences respond to challenge and stimulation as well as toe-tapping entertainment,” said Society of London Theatre president Nica Burns. Including the major state-subsidized venues, more than 3.6 million people bought tickets for plays in the capital, up 26% up on 2008, whilst audiences for musicals were down 2% for the year, but in the final quarter attendances were up 4%. In terms of profits, SOLT has been reporting a year-on-year rise since 2005. The rising cost of tickets has led to increased income even in those years when audiences fell slightly. These are all really quite extraordinary figures.

So what are the implications of these changes?

1) The most obvious is the triumph of Thatcherism. Nothing that the New Labour governments have done in the past decade, despite generous hikes in subsidy, has altered the intense commercialization of British theatre. And, clearly, the current new age of austerity will not change that either. The British theatre system is now thoroughly commercialized from top to bottom. Most subsidized theatres now depend on a tripartite system of funding, which often involves one-third state subsidy from the Arts Council, one-third sponsorship and one-third box office. Many theatres which are less successful in attracting sponsorship must depend for up to 50% of their income on the box office. Obviously, this discourages artistic risks, puts a premium on populist aesthetics, and narrows the repertoire of British theatre. The triumph of commercialism also means that commercial companies now can leave the development of talent mainly to the state-sector, which trains the actors, directors and playwrights, takes all the risks in the development of new work, and then generously shares the profits with private companies. Naturally, the private companies don’t reciprocate.

2) The second conclusion is that the triumph of Thatcherism means that British musicals saved British theatre. Without them, the huge Theatreland buildings would have had to close, and the theatre industry might have gone the way of the mining industry, the steel industry and the textile industry.

3) The third and last conclusion is that the triumph of Thatcherism means that new plays are now almost exclusively the responsibility of the state-funded sector. Whether they are populist or experimental, big stories or nostalgic trips into the past, small plays about “me and my mates”, or large state-of-the-nation tracts, new plays are now all funded by the state, like education, health and defence.

Finally, I’d just like to end on a:

Finale

I started this article by stating that there was nothing so subversive as the pleasure of enjoying commercial theatre. I’m afraid that that is simply not true. The truth is that, pleasure is not innocent. It is always part of a wider experience; in other words, it is always political. Now, I’m as open to pleasure as any other person, and I count performances of The Phantom of the Opera, Mama Mia! and Jerry Springer: the Opera as some of my fondest theatergoing memories. But I’m also conscious of the commercial context of such transactions: the overpriced tickets, the booking charges, the outrageous price of the programme and the eye-popping cost of a drink. I remember the overcrowded toilets, the sullen casts and the mechanical nature of the performances, on stage and in the orchestra pit. I can’t forget the obsessive character of the true fans, the mad messages on their internet sites, and the adulatory exaggeration of their applause. I still recall the discomfort of the whole West End experience, congestion charges, the lack of parking, the suffocating crowds, the stink of cheap food. An individual artwork may be good, bad or somewhere in between. But when it is part of an intensively commercialized system, the experience of the individual spectator is one of suffering as well as pleasure. In fact, you could be forgiven for thinking that the pleasure is a compensation for the misery. That’s the way the system throws its dogs a bone. The relentless pursuit of profit offers the consumer a glimpse of pleasure, but its main aim is to make their wallets lighter. In this political context, when musicals and West End plays are part of a massive money-making machine, the experience of the spectator is less than pure enjoyment. So I’d like to end on a nicely discordant note. If the cultural industries can be seen as part of the UK’s innovation and imagination, they are also part of a less savoury side of contemporary culture: rip-off Britain. In this context, the individual spectator might consider that the current new age of austerity could provide an idea opportunity to fight back. So three questions: Shouldn’t we all be campaigning for lower ticket prices, both in the state-subsidized and commercial sector? What exactly are the profits of commercial theatre, and how can the tax revenue on them be earmarked for state-sponsored theatre? If being an audience member in the context of turbo-charged consumer capitalism feels like slavery, when can we expect the slaves to revolt?

© An earlier version of this article appeared as ‘“We were having fun!”: musical discord in London’s West End’, in Claude Coulon and Jean-Pierre Simard (eds), Le Musical: Stage and Screen/Théâtre et Cinéma, Collection Coup de Theatre, RADAC, 2011, pp 91-98.