Angry Young Men

Tuesday 27th April 2010

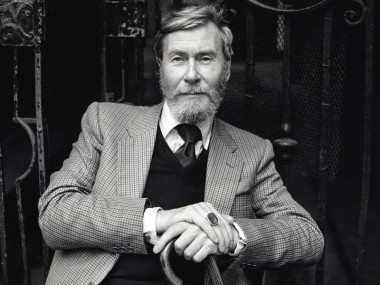

Cultural history is never fair. Alan Sillitoe, the novelist who died yesterday, will best be remembered not just for his books, but for being one of the original Angry Young Men of the late 1950s. Ironically enough, this was a role that he never auditioned for, a label that he never wore and a movement that he didn’t sign up to. Yet the appellation stuck and Sillitoe was remembered for being an Angry Young Man for the rest of his life. So who were these youthful angries and what did they achieve?

The Angry Young Men were defined by their questioning mindsets, and by the fact that they were fed up with what they saw as the failures of traditional British institutions, from Oxbridge to the Foreign Office, to deal with the challenges of the modern world. But if, despite their label, they were rarely red-faced with anger, they were often critical and contemptuous. They were very English in the sense that their discontent was manifested not by calls for revolution, but in sarcasm and irony. Their default mode was a quiet contempt for the fine mess that those in power had got us into.

As well as Sillitoe, the roll call of Angry Young Men usually includes playwright John Osborne, novelists Kingsley Amis, John Braine, John Wain and Bill Hopkins, plus philosopher Colin Wilson (the only one of the group who is still alive). Occasionally, some other figures, such as journalist and playwright Keith Waterhouse, are conscripted. Few can resist including a couple of Angry Young Women, such as Shelagh Delaney, whose debut play A Taste of Honey in 1958 broke taboos about homosexuality and single motherhood, or novelist Doris Lessing, who was then known as a Communist.

The first thing to say about this group is that it was an incoherent collection of individuals. As publisher Tom Maschler, who brought together a book essays by several of them under the title Declaration in 1957, wrote in his introduction to this seminal work, “They do not belong to a united movement. Far from it; they attack one another directly or indirectly in these pages. Some were even reluctant to appear between the same covers with others whose views they violently oppose.”

In fact, the label Angry Young Man came about by accident. In May 1956, when John Osborne’s first major play, Look Back in Anger, opened at the Royal Court in London, the theatre’s part-time press officer, George Fearon, had a problem: he didn’t like the play. So when he had a chat with Osborne, he ended up by saying, somewhat dismissively, “I suppose you’re really — an angry young man.” When he then mentioned this conversation to some arts journalists, the phrase was taken up and applied to almost any writer, whether they were particularly young, angry or a man.

This, at least, was Osborne’s version of the story. Certainly, in the mid-1950s, the phrase was in the air. The first recorded use of Angry Young Man had been in 1951 by the Christian apologist Leslie Paul as the title of his autobiography. So, by the late summer of 1956, newspaper journalists were using the AYM label to describe any artist who was critical of what was then called the Establishment. Newspaper cartoons and feature articles spread the word about these disaffected spirits. It was one of the very first postwar media scandals, creating instant celebrities and a whole cultural phenomenon through savvy spinning and lurid penmanship.

Where the newspapers led, books soon followed. In 1958, Kenneth Allsop rushed into print with The Angry Decade, although a more accurate title would have been The Angry Eighteen Months. He argued that although “anger” was used to advertise these emergent talents, a better word for their “new spirit” would be “dissentience”, a dissent from “majority sentiments and opinions”. Somehow dissent is so much more British than anger or revolt. Evidence of this unquiet, questioning spirit, which was sceptical of postwar British society, can be found in Kingsley Amis’s 1954 book Lucky Jim, which satirized university lecturers and the cultural tastes of educated society. Amis definitely resented being called an Angry Young Man, but his anti-hero Jim Dixon certainly railed against the stultifying conventions of British provincial life.

Like Amis, John Braine was a lower middle-class novelist. His first success was Room at the Top in 1957. This got an enormous boost from being made into a film, with Laurence Harvey, two years later. Poet and writer John Wain was another AYM conscript, but although a chapter of his 1953 novel Hurry on Down was included in the American paperback anthology Protest: The Beat Generation and the Angry Young Men, he was — like Amis and the poet Philip Larkin — more of a university wit than a great experimenter in fiction. Finally, Colin Wilson was a self-publicising philosopher who loudly proclaimed his own genius, and had a massive success with his first book, The Outsider, in 1956. He later wrote books about the supernatural, mysticism and crime. In common with the now largely forgotten Bill Hopkins, he was more concerned with exploring religious and metaphysical values than in writing political manifestoes or advocating a rush to the barricades.

Curiously enough, Alan Sillitoe was not really part of the original AYM phenomenon. Reviews of his two novels, Saturday Night and Sunday Morning (1958) and Loneliness of the Long-Distance Runner (1959), were at first, in the words of the late Humphrey Carpenter, “respectful rather than ecstatic”. It was only when these books were made into gritty, black-and-white, realistic films in the early 1960s that Sillitoe was co-opted into the AYM club.

Although the Angry Young Men were a very diverse group, and more of a media-inspired phenomenon than a real movement, they benefited from two hugely significant political events in the autumn of 1956: the Suez Crisis and the Soviet invasion of Hungary. Although none of their books or plays are about Suez or Communist Totalitarianism, their critical attitudes seemed to give voice to those who were dismayed both by the loss of Empire and by the slowness with which the Establishment adjusted to new global realities. So although Tom Maschler denounced the AYM label as a product of a “lower level of journalism”, he did detect an “indignation against apathy” in 1950s youth culture. The most indignant, of course, was playwright John Osborne. His anti-hero, Look Back in Anger’s Jimmy Porter, was a composite fictional character, a mixture of outsider and rebel. But although Observer theatre critic Kenneth Tynan, in his review of the play, suggested that Osborne was a left-wing playwright, he was merely disillusioned. In common with other Angry Young Men, Osborne was constantly criticised for a lack of commitment to serious left-wing causes, which irritated him because he felt more allegiance to his craft than to a political ideology.

The main achievement of the AYMs was to articulate a vague sense of dissatisfaction which the educated youth of Britain felt in the late 1950s — and their combination of youth, ambition and restlessness did generate a certain creative energy. Class was important. While working-class boys girated to rock ’n’ roll, the university lads listened to folk music and jazz; while street kids liked commercial television, rebels watched the BBC; while Teddy Boys fought hooligan battles at seaside resorts, the angries tended to rebel by reading or writing books and poems. If their politics tended to be anti-American and pro the underdog, they were often surprisingly old-fashioned.

Even during the Suez Crisis, Osborne’s bad-boy image had less to do with politics than with misogyny: in the Daily Mail, for example, he blustered, “What’s gone wrong with WOMEN?” Anger, in the cultural imagination of the time, was a man’s game. Ironically, the AYM myth’s most surprising asset was Osborne himself, ever happy to play up to the role of being what writer Harry Ritchie calls “the angriest young man of them all”. An early example of the rent-a-quote personality, Osborne enjoyed castigating anything from the monarchy to the H-Bomb. But, having played up to the myth, he found it hard to disassociate himself from AYM-dom. The others, from Amis to Sillitoe, more consistently tried to shake off the label. That’s the trouble with media labels — they make good servants but bad masters.

© This article originally appeared as ‘Who are you calling angry?’, Daily Telegraph, 26 April 2010

1 Comment

on Sunday 6th March 2016 at 11:42 am