Beyond Timidity? (New Writing 2004)

Tuesday 1st February 2005

It’s January 2005, ten years since Sarah Kane’s Blasted opened in the tiny Theatre Upstairs studio at the Royal Court. Although this was not the first play of the 1990s to have a raw in-yer-face sensibility, it quickly became the most notorious. Kane was soon patronizingly characterized as the “bad girl” of British new writing for the theatre, a reputation which her last two plays, Crave (1998) and 4.48 Psychosis (2000), with their obviously experimental approach to theatrical form, did much to challenge. At the time of her debut, Kane’s work seemed to be typical — in its dirty realism — of British new writing; gradually, it has become clear that she was the exception to the rule that naturalism, well, rules. In the years since her suicide at the age of 28 in 1999, British new writing has expanded apace — but how does the scene look at the start of 2005?

The first paradox is that although Kane’s work has been extensively staged in many different versions all over Europe and beyond — recently, she has more often been produced in Germany than Schiller — her importance in British theatre has already faded. Although, in September 2000, a 15-year-old newcomer, Holly Baxter Baine (whose Good-bye Roy was part of the Royal Court’s high-profile Exposure season of young writers) could convincingly say that her favourite playwrights were Brecht and Kane, the fact is that Kane was soon worshipped more in the academy than by practitioners. Since 1999, her work has practically never been performed in Britain, except for the Royal Court’s memorial season in April-June 2001. Even so, this theatre only staged three of her five plays, and only one, Blasted, was given a new production. (Crave and 4.48 Psychosis were revivals of the original productions, and her other two plays were only given rehearsed readings.) Apart from a couple of new versions by the Glasgow Citizens theatre, and a production of Crave by Matt Peover’s Liquid Theatre company, there have been no other stagings. Perhaps for this reason, there remains a great deal of ignorance about her work — despite her legendary reputation. In their glossy book, Changing Stages (2000), for example, Richard Eyre and Nicholas Wright wrongly summarize the plot of Blasted as “an abusive relationship between father and daughter”. Now that’s what I call a howler!

One reason for the lack of Kane productions is British theatre’s relentless search for novelty. The explosion of creativity in the new writing scene in the mid-1990s — which I have documented in my polemical account, In-Yer-Face Theatre — spurred theatres to look for the next new talent, with the result that very few new plays ever get a revival. So intense is the competition between theatres to stage the new that once one has put on a new work no other theatre will touch it. Exceptions such as Joe Penhall’s Blue/Orange and Charlotte Jones’s Humble Boy are just that: exceptions. Nevertheless, by the end of the 1990s, there was more new writing in British theatre than ever in its history. Names such as Sarah Kane, Mark Ravenhill, David Greig, Philip Ridley, Conor McPherson, Anthony Neilson, Martin McDonagh, Phyllis Nagy, Patrick Marber, Tanika Gupta, David Eldridge, Marina Carr, Rebecca Prichard and Roy Williams became known, and discussed, outside the narrow ambit of new writing specialists. It’s relatively easy to make a list of more than 150 new British playwrights who have made their debuts in the past ten years. It has also been calculated that between 500 and 700 writers of stage plays, radio plays and television drama make their living from writing in Britain. These are really remarkable figures, and unique in Europe. All this is evidence of a buzz in the air: as new work attracted the attention of the general public, it also woke up the funding authorities. And pretty soon other venues joined in. Across the country, there have been abundant crops of new writing programmes, new writing competitions and new writing festivals. New writing is now better funded, more diverse and more widespread than ever.

At the same time, with the new millennium starting, signs of crisis also appeared. Sure, the emergence of even more new talent — such as Simon Stephens, Zinnie Harris, Enda Walsh, Abi Morgan, Gary Owen, debbie tucker green, Rebecca Lenkiewicz, Joanna Laurens — was heartening, but such a blossoming of new work couldn’t conceal the fact that not all was rosy in the garden. The reason for the renewed crisis in young writing was not that young playwrights had nothing to say, but that they chose to say it in conservative and untheatrical ways. The new millennium seemed to encourage most playwrights to reheat traditional aesthetic repasts and not stray very far from the familiar taste of naturalism, social realism and linear plays about “me and my mates”. Nevertheless, it is encouraging to know that a few writers to dip into the dimension of the imagination, drawing on more Continental traditions of surrealism and absurdism. Good examples of this new magic realism from 2002 include Royal Court plays such as Jez Butterworth’s Night Heron and Nick Grosso’s Kosher Harry, as well as Caryl Churchill’s A Number. (In this, as in her other recent work, Churchill has demonstrated that age is no barrier to innovation, and has called into question the habit of awarding the title of best living British playwright exclusively to men such as Harold Pinter or Edward Bond.) Unusually, innovative plays such as hers also did good box-office.

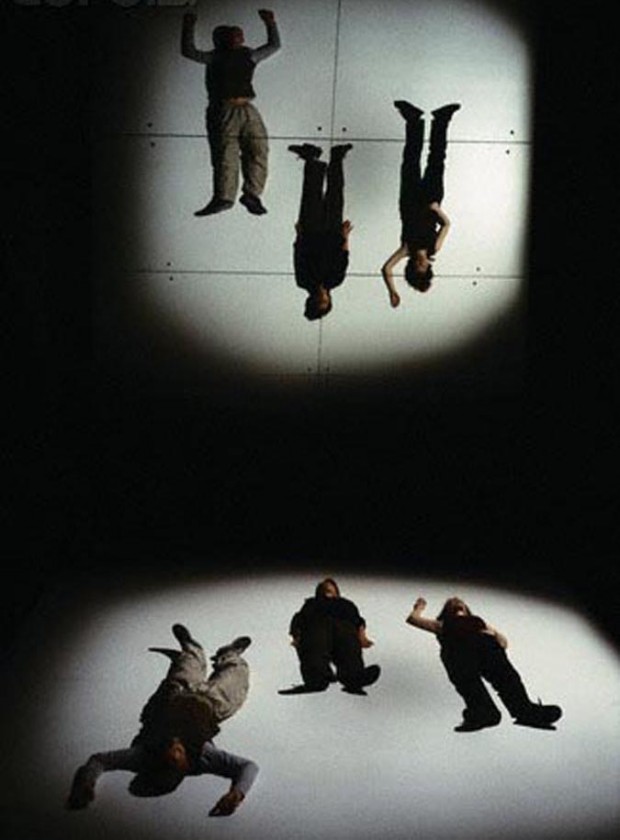

In the Royal Court’s 2004 Young Writers Season, two plays — Clare Pollard’s The Weather and Robin French’s Bear Hug — expanded on tawdry sensibilities by going beyond council-estate naturalism and using boldly theatrical devices such as an on-stage poltergeist and a teenager turned into a bear. Even in the West End, there was room for a more poetic sensibility, with revivals of Moira Buffini’s Dinner (2003) and Marina Carr’s By the Bog of Cats (2004). At the same time, the continued success of new(ish) physical theatre or live art companies such as Frantic Assembly, as well as veterans such as Complicite and Forced Entertainment, showed that a fusion of text, dance and music was still one of the best ways of avoiding the banality of suffocating dramas set in sitting rooms dominated by centre-stage sofas.

Elsewhere, the events of past two or three years have encouraged critics and commentators to applaud a revival of political drama, usually seen as theatre’s response to 9/11 and the subsequent War on Terror. For the first time in ages, the Edinburgh Festival fringe has engaged with the wider world, while all over Britain theatres have been putting on anti-war plays. Often hyped as a rediscovery of radicalism, this trend is, however, still being held back by the dead hand of naturalism and by the popular notion that verbatim docu-drama is the best way of staging ideas. But although it was good to see theatres respond so quickly to events, the obsession with docu-drama could sometimes be self-defeating: the Tricycle Theatre’s Justifying War was staged before the Hutton Enquiry had published its report, and the play strongly implied that the government had done wrong, but the actual conclusion of the Hutton Inquiry came to the opposite verdict, and exonerated Blair. This time, reality outwitted the theatre of reality.

In terms of aesthetics, the trend towards verbatim theatre, where most or all of what is spoken on stage is based on true statements, also seems to put the imagination on the back burner. Political plays such as David Hare’s The Permanent Way (2003) and Stuff Happens (2004) or Victoria Brittain and Gillian Slovo’s Guantanamo: “Honor Bound To Defend Freedom” (2004) come across as powerful public forums, but they can’t be said to stretch drama’s aesthetic boundaries — or even to suggest ways of changing the world. Like Reality TV, they simply tell us what we already know.

Only when playwrights mix imaginative populism with radical ideas does political theatre really get a shot in the arm. After all, there’s nothing quite as subversive as blending the joy of good ideas with a real sense of fun. The whole point of political theatre is that life is about much more than what happens on the domestic front. Since audiences nowadays would run a mile rather than sit through the worthy, wordy and often woolly “state of the nation” plays that mercifully went out of fashion soon after the fall of the Berlin Wall, how do you write big plays about big subjects? One common cop-out is to say that all plays are political. This rip-off of the old feminist slogan that the personal is political is, however, totally self-defeating. If all plays, no matter how domestic, are political, then no plays are political. A better way of defining a political play might be to insist that it should offer both explicit political ideas and some hope of change. By this definition, the problem with verbatim theatre is that it merely reflects reality, when the point, surely, is to change it.

What new writing in British theatre needs most of all is to shake off its habitual timidity, and to explore the world’s more dangerous shores. Isn’t it odd that there have been no British plays about global warming? Or corporate manslaughter? Or mixed-race identity? Who, apart from a couple of greyhairs, ever questions the liberal consensus in the British theatre system? Another way of defining political theatre is not only by its capacity to suggest change, but also by its ability to expand the imaginative horizons of its audiences, contesting the closing down of the imagination by the commercial mass media. At a one-day symposium, held at the RSC’s Stratford-upon-Avon base, in October 2004, playwright Sarah Woods asked: “Why have a pool, if you only use it as a foot-spa?” It’s a striking metaphor, and one which urges writers to expand their artistic canvas. In this sense, what matters is vision.

I remember the press night of Leo Butler’s Redundant at the Royal Court, this time on its main stage. Okay, it was a classic dirty realist play set on a council estate, a familiar howl of rage. But it did also have an intensely visionary moment: at one point, the old granny turns on the rest of the cast and harangues them, “Someone should bomb this bloody country. That’d wake us up a bit. Saddam Hussein or someone. IRA, bleedin’ whatsisface? Bin Laden. He could do it. Drop a few tons of anthrax. Teach us what it really means to suffer.” On the press night, the line mentioning Bin Laden was cut — well, you can understand why: the date was September 12, 2001 (or 9/12). But the speech does show how writers can connect with global events when they let their imaginations off the leash. Even more profoundly, a playwright such as Mark Ravenhill can justifiably argue that one of the most theatrical and thrilling responses to 9/11 was Churchill’s Far Away — and that was first staged in November 2000, almost a year before the event.

Likewise, some of the most thought-provoking plays about the War on Terror are not the lurid satires that preach to the already converted, but reworkings of ancient Greek tragedies. For example, Martin Crimp’s Cruel and Tender, a free adaptation of Sophocles’s Women of Trachis (2004), says more about the spirit of the age than most recent heavy-handed caricatures of Blair and Bush. And the same writer’s short text, Advice to Iraqi Women, is a perfect example of how resonance is achieved by indirection and metaphor. In a similar vein, director Dominic Dromgoole has pointed out recently that “When Shakespeare wrote his great historical plays, he chucked everything in: nonsense about witchcraft, battle scenes, father-son stuff, pageants, philosophical introspection. History, the record of facts, was a release for the great heap of images inside him — not a clamp on his imagination.” In 2005, perhaps the best antidote to timidity in British new writing is the irrepressible, untamed quality of the imagination — and perhaps the best mission for a theatre of the future is no less than the project to create a new idea of the human.

© Aleks Sierz