Let Battle Commence: New Writing in 2007

Tuesday 1st May 2007

It is well know that British new writing for the theatre has been enjoying an unprecedented boom in recent years. There is now more new writing than at any time before: everywhere you look, both in and outside London, there are new writing festivals, new writing bursaries, new work for kids and new plays on stage. What is less well known is that there is an aesthetic struggle at the heart of new writing, a battle between the literalists and the metaphysicals.

The Literalists

Of course, we are all familiar with the literalists. This label refers to the Great British tradition of naturalism and social realism. Its part-time grandparent is George Bernard Shaw and its fathers are John Osborne and Arnold Wesker. It’s a theatre style that Scottish playwright David Greig calls “English realism”: This new writing genre, which has thrived in subsidised theatres for the past 50 years, shows the nation unto itself. It voices debates and deals in issues. Its stories are linear and based firmly on a recognisable social context. Its dialogues are convincing and down-to-earth. It is distrustful of metaphor and suspicious of fancy foreign work, which is usually characterised as effete, abstract and humorless. By contrast, English realism is muscular, earthy and wry. With English realism, concludes Greig, “The real world is brought into the theatre and plonked on stage like a familiar old sofa.”

You can see his point. Despite the deluge of the new, most new work is written in this familiar English tradition. And there’s a real failure of theatrical imagination at the heart of the whole literalist endeavour. Most new plays are small in every respect: cast, space and theatrical ambition. Soapy dramas for couch potatoes. Whether they are about “me and my mates”, teen angst or underclass violence, they normally squat on territory that is already known — there’s little sense of exploration, or experiment, or excitement.

Boundaries remain unbreached; fantasy is grounded by the twin ballast of naturalism and social realism. And while political theatre has experienced a boom in the wake of 9/11, it too usually remains chained to the literalist tradition. Think verbatim drama, think docudrama — theatre’s answer to reality tv. As ever, in this genre, what you see is what you get. Indeed, often what you see is all there is.

The Metaphysicals

The metaphysical wing is less familiar. It’s a good label because it calls to mind the tradition of metaphysical poetry, which was championed by TS Eliot in between the wars, and was the subject of a highly influential book of collected poems, edited by Helen Gardner and originally published in 1957, the year after the premiere of Look Back in Anger. In her introduction to these 17th-century poets, Gardner stresses their wit, their conceits and their imagination, and argues that they typically expressed “deep thoughts in common language” and “extraordinary thoughts in ordinary situations” (24).

She also contrasts the “strenuous” and “masculine” style of playwright and poet Ben Jonson with the more elaborate conceits of the true metaphysicals, such as John Donne and Andrew Marvell (18–19), who (presumably) are more “effete” and “feminine”. Donne, of course, was a “great frequenter of plays”, and Shakespeare — with his mix of wild imagination, philosophical speculation, ghosts, history and social realism — can easily be seen as the grand old man of the metaphysical tradition.

But if this label doesn’t appeal, maybe another would serve equally well. Playwright Anthony Neilson suggests “psychoabsurdism”, yet absurdism would do equally well. Or surrealism; or monsterism; or just plain non-naturalism. Or even leftfield theatre. The labels matter a lot less than the work itself.

Crimp’s Attempts

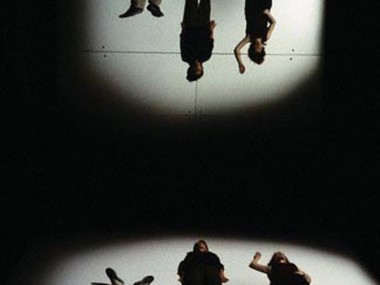

On the Encore Theatre Magazine website, the battle between these two great traditions is joined over Katie Mitchell’s current National Theatre revival of Martin Crimp’s 1997 play, Attempts on Her Life. If ever there was an anti-naturalistic play, it’s this one. With its open text, and disregard for the usual literalistic markers of a naturalist play (characters, scenes, dialogue and plot), the piece positively heaves with potential for imaginative stagings. And, in Mitchell’s new version, it comes across as a phantasmagoria of video effects, fast-paced acting and visual bravura. It is theatrical theatre par excellence. You couldn’t make a film of it.

Of course, the National — so frequently caricatured as a staid old institution — has, under the artistic directorship of Nicholas Hytner, contributed immensely to the recent consolidation of the metaphysical tradition: think of Mitchell’s Waves (2007). Think also of Jerry Springer: the Opera (2003). And of associate director Tom Morris’s championing of innovative theatre companies such as Shunt, Kneehigh, Punchdrunk and Improbable, all of whom have been welcomed into the National fold.

In a stark illustration of how the National has turned the tables on other so-called cutting-edge theatres, it is useful to quickly and perhaps unfairly compare two versions of Chekhov’s The Seagull. At the National in 2006, Crimp and Mitchell’s version was fast, innovative and shocking; at the Royal Court in 2007, Ian Rickson’s was slow, clichéd and traditional. One made you sit up; the other made you yawn.

New Arrivals

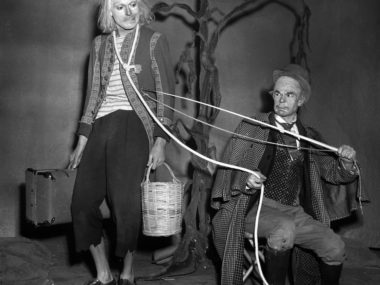

With the arrival of Dominic Cooke at the Royal Court in 2007, things look set to change. That theatre, once the epitome of forward-looking excellence, has recently begun to look lame. In 2006, its sell-out show was Rock ’N’ Roll by Tom Stoppard, a fine play but hardly innovative or contemporary; in the same year, Tanika Gupta’s Sugar Mummies also sold out, despite the fact that some critics saw it as clichéd and soapy. At first glance, Cooke has begun well. His first mainstage show, the National Theatre of Scotland’s revival of Anthony Neilson’s 2004 play, The Wonderful World of Dissocia, is a slap in the face of literalism. And his immediate plans, to stage Crimp’s translation of Ionesco’s Rhinocerous, and to transform the theatre space to accommodate Mike Bartlett’s My Child, sound very promising.

Other examples of regime change, at the Bush and the Soho, also look encouraging. Lisa Goldman, who began work as the new head of the Soho in 2007, has programmed Philip Ridley’s Leaves of Glass as her first play, and then followed this up with two other plays that sound as if they have their fingers on the pulse of the contemporary: Oladipo Agboluaje’s The Christ of Coldharbour Lane and Hassan Abdulrazzak’s Bagdad Wedding.

At the Bush, Josie Rourke has taken over from Mike Bradwell, and promises not only to continue this venue’s fine tradition of innovative new work, but also to head the search for a bigger theatre space. For some years now the Bush has been aching to cast off its fringe status, and become an off-West End venue (in size if not location). Finally, David Lan’s use of his newly refurbished Young Vic theatre has also been experimental. By giving room to Dennis Kelly’s provocative and formally exciting Love and Money and to debbie tucker green’s Generations, in Sacha Wares’s thrilling production, he has shown his support for new writers. In the Big Brecht Fest, he has staged the German master’s shorts in translations by Rory Bremner and Martin Crimp, using directors such as Mitchell and Joe Hill-Gibbins.

Five years after picking a title, and issuing a manifesto, the Monsterists — a group of playwrights, including Roy Williams, Richard Bean and Ryan Craig, who are dedicated to staging large-scale work — continue to make their presence felt. In 2006, one of their number, David Eldridge, had his play, Market Boy, staged on the massive Olivier space at the National, and Moira Buffini’s Dinner had a respectable West End run at the Wyndham’s three years before that. In the playtext, Buffini notes that her revenge fantasy is set in a no-place “surrounded by darkness”. Good to see a metaphysical play in the West End.

Elsewhere, it is likewise good to note the presence of metaphysical elements in other recent work. As ever, the market leader is Caryl Churchill. Her 2006 play, Drunk Enough To Say I Love You?, was hammered by some of the critics, but its text is an imaginative account of postwar global politics mercifully free of any verbatim claptrap. Mark Ravenhill’s pool (no water) (Frantic Assembly, 2006) and Product (Traverse, 2005) both show distinctly Crimpian influences, while Conor McPherson’s The Seafarer (National, 2006) had an onstage Lucifer, and the Scarecrow in Marina Carr’s Woman and Scarecrow (Royal Court, 2006) was the grim reaper. A great season for ghostly presences. Playwrights such as Georgia Fitch (Adrenaline… Heart) and Kay Adshead (Bones) are at their best when their poetry fractures the form of their plays.

Conclusion

Whether the current grapple between metaphysicals and literalists results in better new plays is as yet uncertain, but it will have done its work if it concentrates minds on that often neglected side of theatre-making: aesthetics. As Dominic Dromgoole, who is championing new work as well as that of the bard at Shakespeare’s Globe, says: “At this peculiar moment when we are all being asking to club together yet again and commit murder [in the War on Terror] in the name of some gang we do not subscribe to and detest, to weaken the strength of another gang we loathe just as heartily, now seems as good a moment as any to re-attest the importance of the individual aesthetic.” (306)

References

Anon, ‘The Battle Commences’, Encore Theatre Magazine, www.encoretheatremagazine.co.uk, 18 March 2007.

Dromgoole, Dominic, The Full Room: An A-Z of Contemporary Playwriting, rev edn, London: Methuen, 2002.

Gardner, Helen (ed), The Metaphysical Poets, rev edn, Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1972.

Greig, David, ‘A Tyrant for All Time’, Guardian, 28 April 2003.

© An earlier version of this article appeared as ‘Let battle commence: new writing 2007’, Performance Prompt, Rose Bruford College’s Theatre Futures website, www.theatrefutures.org.uk/performanceprompt, April 2007.