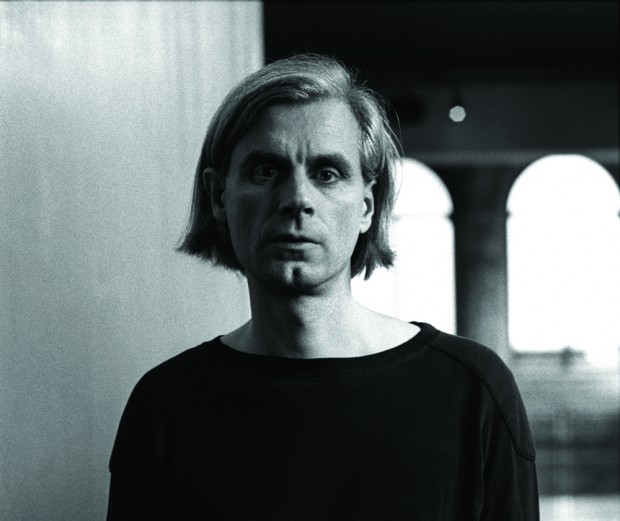

Martin Crimp: Attempts on His Life

Sunday 1st October 2006

My book about Martin Crimp has concentrated on his work. Biographical details, anecdotes about his life and clues to his character have been few. For good reason. In The Misanthrope, for example, Crimp parodies the biographical approach to playwriting when Covington says: ‘It’s directly based/ on my own personal experience.’ To which Alceste replies: ‘Well that’s often the case’ (120). To suggest some of the problems of relating the life to the work, especially when the life is relatively uneventful, I will now risk adopting a Crimpian strategy to describe his life as a writer. Since in Attempts on Her Life, each of the seventeen scenarios about Anne obscures as much as it reveals, it seems perfectly apt to create seventeen mini-scenarios about a character called the Writer, and a would-be biographer called the Critic.

1) The project

For his next book, the Critic decides to focus on an individual playwright, the Writer. But he is perturbed by the popular postmodern theory that proclaims The Death of the Author. What if the Writer hasn’t written his plays? What if language has merely spoken through him? The next day, the Critic catches a glimpse of the Writer at the opening of a show in London. Phew, at least he’s still alive. But what is he like as a person?

2) The school

The first thing that the Critic establishes about the Writer is that he went to the same school as another famous writer. So he then scans the Writer’s work for clues to his upbringing, his family, his school. With conspicuously little success.

3) The background

For background, the Critic approaches the Writer’s Agent. Does she have any background information on him? Like what? Oh, you know, feature articles, or profiles, or even revealing interviews. After a couple of days, the Agent gets back to the Critic. No, there’s no background material on file. In the past, muses the Critic, writers could appear as The Underground Man, The Superfluous Man or The Man without Qualities. Today, the Writer appears as The Man without a Background.

4) The Academic

The Critic contacts the Academic. He’s heard that the Writer, who is fast becoming his playwright, has visited the Academic’s university and given a talk to his students. Surely, he must have spoken frankly about his life. So the Critic asks the academic for a recording of his talk. The Academic tells him that the Writer refused to be recorded, and that all he remembers is that he repeatedly insisted that he is a ‘satirist’.

5) The translation

The Critic finds out that the Writer has given his most candid interview to a Foreign Critic. Seeing that the Foreign Critic has published the interview in a language the Critic cannot read, he contacts him and asks him for the original transcript. But the Foreign Critic tells him that the original transcript vanished when his computer was stolen. And he didn’t keep the tapes. But he offers to send the Critic the translated version. Now the Critic has to find a translator to translate the translated interview back into English. In the process of retranslation, much is lost. The Writer remains elusive.

6) The programme note

The Critic is asked to write a programme note for a revival of one of the Writer’s plays. This forces him to look in detail at his work. He is struck anew with a sense of its passion, its fierceness and its cruelty. He struggles to reconcile this with his personal knowledge of the Writer, who always appears detached, gentle and kind. It is time to stay up all night tussling with ideas about the workings of the human imagination.

7) The newspaper article

As the Writer’s new play is about to be staged, The Critic tries to place an article about him in a Sunday broadsheet. But he’s asked to interview the director instead. He does so, and writes an appreciative piece about the director’s skills. In it, he includes some quotations from the Writer. The article comes back from the editors. What’s all this stuff about theatre? What we want to know is about the director’s private life. What does he drink? How badly does he dress? Who is he sleeping with? To accommodate this extra material, the Critic has to cut the quotations from the Writer.

8) The festival

On a trip abroad, the Critic and the Writer are both guests of the same theatre festival. They appear on the same public panels, are interviewed by the same journalists and drink the same kind of wine. For a short while they are treated as heroes — then it’s time to come home. On their return, the Critic struggles to create a picture of the Writer’s character. He gives up when he realises that, in the highly artificial atmosphere of a foreign theatre festival, they were both playing a role.

9) The research

On a research visit to the Theatre Museum, the Critic discovers a rare newspaper article written by the Writer. It is an ironic account of his imaginary meeting with a long-dead, now classic, Foreign Playwright, whose work he has translated. In it, the Foreign Playwright is made to say: ‘No personal questions! Is this taste for sleaze/ really essential to British journalese?/ This nation must be utterly mind-fucked/ to salivate over people’s private sexual conduct.’ The Critic abandons his plan to ask the Writer about how his private life has influenced his work.

10) The music

Aware that the Writer is an accomplished musician, the Critic scans his work for evidence of a musical ear. Everywhere, references to classical music jump out at him. Suddenly his work seems to be all about music and nothing else. Even the dialogues seem like songs; while reading, the Critic finds himself humming them like tunes.

11) The opening night

The Critic attends the first night of a play by a young German Playwright. He finds himself sitting directly behind the Writer, the English Writer — his Writer. As the German play unfolds, the Critic not only watches the new play over the head of the Writer, but also sees it exclusively through the prism of the Writer’s work. He leaves the theatre with a distinct feeling that he hasn’t really appreciated the German Playwright’s work for its own sake.

12) The supermarket

As word of the Critic’s book spreads, he hears many reports of sightings of the Writer. Oddly enough, they all seem to occur in a supermarket. Is this writer a particularly fanatical shopper? Or more than usually hungry? Or are supermarkets simply one of the few public places left where chance encounters actually happen?

13) The family

The Writer is family man. The critic meets the Writer’s family on more than one occasion. And nothing he sees or hears when meeting the Writer’s family has the slightest relationship to the Writer’s work. Is it possible — has the Writer really purged himself of the biographical fallacy?

14) The postcard

The Writer sends the Critic a picture postcard. The Critic examines this for clues. Is there a subtext beneath the cheerful greeting? What does the image on the postcard mean? What clues does the handwriting give to the Writer’s character? The idea of analysing the Writer’s handwriting only shows the Critic the absurdity of his obsession with the life — better stick to the work.

15) The obit

The Critic learns that two Spanish Academics have interviewed the Writer. So how was he? Oh, ‘He was most helpful and generous with his time, specially considering that he had arrived only the day before and had the journalists waiting for him,’ they reply. When the Critic tells the Writer about this, he summarises their response as: ‘Tired but helpful.’ The Writer laughs: ‘He was tired but helpful — sounds like a good obituary.’

16) The interview

The Critic interviews the Writer for a magazine article. During the course of the interview, he struggles to find a way of describing the Writer’s gestures, his taste in mineral water and his dress sense. At one point, in what seems like an unthinking gesture of generous revelation, the Writer says: ‘It’s a question of my temperament — I always want to take the devious route.’ As a psychological key, it’s not much, but it’s the nearest the Critic gets.

17) The end

The Critic can’t think of a good way of finishing his book. So he decides to write an entertainment based on the Writer’s own work. But much as he flatters himself on his own satirical skills, he slowly realises that his attempt to get under the skin of the Writer is, alas, only partially successful. In the end, any resemblance between these characters and any person living or dead is purely…

© This article originally appeared as ‘Appendix: Attempts on His Life’ in Aleks Sierz, The Theatre of Martin Crimp (Methuen Drama, 2006), pp 221-225.

See also: