Martin Crimp on Not One of These People

Saturday 29th October 2022

The fictional world is our world, but at the same time it’s another place. We want our writers to invent interesting characters, gripping plots and to take us to unexpected locations. We want them to delight us, and sometimes to fright us. We want to immerse ourselves in their inventions, lose ourselves in their fictions, and explore their newly created worlds. But are writers allowed to say anything they want? Is there a limit in our progressive and increasingly sensitive society on what they can invent? Would any theatre in Britain stage a play about young black women which was written by a old white man? On the website of the Royal Court, the venue for playwright Martin Crimp’s latest play, Not One of These People, the publicity asks: “Is it appropriation to invent a voice — or is it an act of empathy? If a playwright’s job is to make dialogue, is there a limit to how many characters she / he / they are entitled to invent?” With the play, which the author himself performs for a short run next week, about to open, I talked to him about its form and its themes.

ALEKS SIERZ: Your latest play has its origins in the plight of theatre at the start of the pandemic — is that so?

MARTIN CRIMP: Yes, that’s right. When all theatres were closed during the first lockdown [in March 2020] nobody knew when, and how, things would get back to normal. So I was talking with Vicky Featherstone [artistic director of the Royal Court theatre] about making work that could be performed as soon as conditions eased and audiences could return, even with social distancing. I was wondering what would be the ingredients of such a piece? Firstly, to avoid physical contact between actors and to have little or no rehearsal a text could be read off the page rather than learnt and rehearsed. Secondly, you could have a text of long duration — maybe even several hours — so that small audience groups could enter at intervals, sampling the text, as it were, before leaving to let the next group in.

What about the content of the piece?

To answer that I have to track back a little. A while ago, I had an encounter with a group of young writers at the Royal Court and a burning question for them was: “What am I entitled to say when I write?” They were talking about who they could “give voice” to, or not. And I was quite surprised; I hadn’t realized this was such a hot topic. At the time, I said to them: “Well, you write what you like, and the culture around you will decide whether it’s valid, or appropriate, or whether it works.” But when I went away and thought about this, this question about who can write what, the more I thought about it, the more I felt my response to them had not been adequate.

How do you mean?

I’m aware of course that there are some very reactionary writers out there who get grumpy and say, “Well, anybody can write anything.” But you can never write absolutely anything — that’s impossible. Only in Borges’s infinite library can anything in an absolute sense be written: I mean, could Franz Kafka write absolutely anything he liked? — no. Could Virginia Woolf write whatever she liked? — no. Because they, and we, are particular people at a particular time and a particular place, so there are always limits. At the same time, you have to take account of the human imagination. The human imagination is immensely complicated, immensely unfathomable, and it’s the thing we value in writers and artists. Their ability to imagine.

The publicity for your play mentions “empathy”…

Yes, one of my favourite images for the human imagination is that of the city, which I use in my play The City, a place where every writer and every artist creates their own imaginative world that they then investigate. Or, another way of looking at it is that it’s a labyrinth, which you investigate with your little torch and your spool of thread, and you look down various passages, where sometimes there’s gold and sometimes a monster. Everybody has their own imagination, and this enables everybody to make discoveries, but at the same time, beyond imagination, there are also rules. And all writers and artists set their own rules and will work within those rules. Although all this sounds very private, the thing about the imagination is that it can be shared among other people. So although I don’t know anything about 1920s Bloomsbury or Prague I can still enter the mind of Mrs Dalloway or Joseph K. I know nothing about ancient Greek battles but I can enter the mind of Achilles sulking in his tent. So beyond biography there is the imagination and this bigger world so that, I suppose, is my point of departure for trying to write this new play, which is a response to the questions raised by the young writers I mentioned.

How did these ideas affect the piece you were thinking of writing?

Originally I was going to write a thousand different characters, each with a few lines of dialogue. But I never made it to that number. When I got up to 300 in August [2020] I had a lot of material, but I didn’t want a round number. So I stopped, having essentially invented 299 different people, and I call it Not One of These People because obviously I’m not any of those people, but maybe I’m also all of those people. My problem was that, having written all of these characters, I didn’t know how to put all of these people on stage. Because of COVID restrictions, I thought that actors could just sight read these lines of dialogue, so they wouldn’t have to spend ages preparing, but I was never quite sure about how to do it. Time passed, Vicky was still keen to produce the work, but, like myself, not sure what a mise en scène would look like. But then the Québécois director Christian Lapointe intervened, with a concept that brilliantly links the text to contemporary internet culture.

How did that happen?

Christian is the artistic director of Carte Blanche in Quebec City. He has staged several of my plays in Canada — In the Republic of Happiness and When We Have Sufficiently Tortured Each Other — but I really didn’t know much about him until we met on zoom. I had just had my first face-to-face meeting with Vicky after the lockdown and we were starting to discuss how we might perform this text. So I met Christian on zoom and I found him immensely sympathetic and intelligent, and he also had this brilliant idea about staging the piece. He said: “Take a look at this website called This Person Does Not Exist.” So I did that. Nothing appears on the website except for a hyper-realistic photograph of a face, and when you click refresh another completely different face appears.

So how…

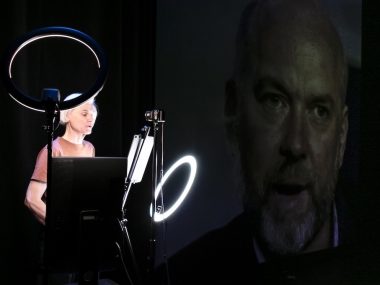

Christian said: “Do you know what you’re looking at?”, and I said: “I have no idea.” He said: “None of these people exist — they are all generated by artificial intelligence.” Then he said: “Well, we can cast your play with these invented people from this website and you, Martin — would you read their lines?” I found the prospect terrifying, but I immediately saw that he was right because the other thing that my piece is doing is that it is stripping naked the process of making theatre. Because normally the writer hides, and instead all these other people, the actors, appear on stage, and we invest in them and believe that they are real. So I could see that although it was frightening it was the right thing not to hide, but to appear on the stage. From this new perspective, the play was no longer a text of long duration, but a strange kind of 90-minute monologue performed by me.

So you performed the piece for Christian in Quebec?

That’s right, on 1 June this year for just one performance. Then Christian performed it twice there in Québécois French, and now I am doing four shows at the Royal Court.

So you read the lines of your text and images generated by AI appear on a screen as if they are the characters who are talking…

Yes, the 299 people that I created appear during the piece which is divided into three sections in my mind, although in the performance these divisions might not be so clearly visible. These three sections are part of the rules, constraints if you like, that I set myself when writing. The first 100 are what I would describe as “cultural toothache”, which is what other people call culture wars. So you might find a young woman saying that while she does not support death threats, if you say certain things you will receive them. Or a man might be saying that gender is just a social construct in order to defend his own appalling masculine behaviour. The second 100 are inspired by Speak Bitterness, a piece by Tim Etchells and Forced Entertainment [1994] which made such a profound impression on me, so they are various confessions. Confessions are a powerful tool. And the last section of 99 people is based on the notion of chance because I thought that’s something that has a long history in playwriting, for example Oedipus at the crossroads who kills his father by chance. Or is it fate? But I’d like to stress that the play is not just a reading; it’s not just an artistic installation; it has drive and development.

How does Not One of These People relate to the questions asked by that group of young writers which first gave you the idea?

Good question. I think the play is constructed precisely on these fault lines of who’s entitled to say what or perform what, and my hope is that it is a unifying rather than a divisive gesture and that it will enable writers who see it to consider their positions and relationships to characters, to theatres and to the world. Playwrights shouldn’t be frightened, they shouldn’t have anyone looking over their shoulders and they should be encouraged to write whatever they want to write. Hopefully the quality of that writing is what breaks through barriers or prejudices that people might have. It’s a sad thing that we live in a very divided world where people have all sorts of fights while at the same time rightwing governments are making headway and disadvantaged people are just dumped in the dirt.

Well recently you did create an interesting example of cultural fusion and diversity on stage. I’m talking about your work with director Jamie Lloyd on Cyrano de Bergerac, which was a huge hit in the West End and Broadway. Do you have any plans to collaborate with him again?

I’d love to work with him again, and we do have regular conversations that explore a range of possibilities, but there is nothing definite yet. I can also tell you that, after my previous collaborations with George Benjamin, such as Written on Skin, there will be a new opera next year, which will premiere at Aix-en-Provence and then come to the Linbury Theatre at the Royal Opera House. But you’ll have to wait for the official confirmation of the title and dates.

- The Theatre of Martin Crimp.

- This interview first appeared on The Arts Desk