Reality Sucks (New Writing 2007)

Thursday 1st May 2008

The distinguished film director David Lean once said, “Reality is a bore.” He was talking about the fashion in 1960s cinema for social realism, for kitchen-sink drama, for angry young men. You can see his point. Ever since the advent of John Osborne’s Look Back in Anger — whose 50th anniversary in 2006 was celebrated in a rather listless fashion by Ian Rickson, the Royal Court’s outgoing artistic director — British theatre has been in thrall to a mix of social realism and naturalism whose hegemonic power remains a problem even today. So pervasive is this strand in the culture that the title of the Arctic Monkeys 2006 CD is Whatever People Say I Am, That’s What I’m Not, a direct steal from defiant Arthur Seaton, played by Albert Finney in Karel Reisz’s 1960 social-realist film Saturday Night and Sunday Morning. Today, given the anxieties created by the digital age’s affront to old and established views of reality, and to the ongoing global uncertainties unleashed by the War on Terror, the British public’s desire for reality is more intense than ever — and this is manifested not only in a seemingly insatiable appetite for reality TV, but also in a need to be assured that the best theatre is somehow “real”, explanation enough perhaps for the current vogue for verbatim drama.

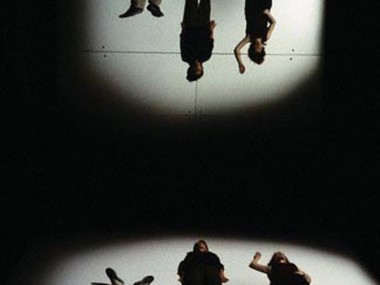

But the hegemony of social realism and naturalism is, like other hegemonies, not just an innocent preference for one aesthetic over another. No, it’s a cultural mindset which only works by excluding, by marginalising, by belittling any theatre that doesn’t obey the right dress code. Like an attack dog, it needs victims. In 2006, for example, director Katie Mitchell staged a new translation of Chekhov’s The Seagull at the National Theatre. Out went all the clichés associated with this master of naturalism: there were no samovars; no chirping birdsong; no melancholic silences. Using a radical new translation by Martin Crimp, which ditched the patronymics and Russianisms so beloved of British audiences, the production was an aesthetic success — and a slap in the face of this flagship theatre’s regular patrons. But one smack can provoke another. Mitchell received hate mail, with one spectator scrawling “RUBBISH” on their programme and sending it back to her. A similar confrontation between this director and one part of the National’s audience took place in 2007, when Mitchell staged a rare revival of Crimp’s 1997 masterpiece, Attempts on Her Life. This time both play and production (which saw the actors used as film-makers who videoed parts of the stage action which were then projected onto massive screens) proved scandalous. Critics savaged the production: one called it a woeful example of “Mitchellitis — a dreadful form of directorial embellishment” (Evening Standard) and another “two hours of debasing trash” (Daily Mail), with Crimp’s writing characterised as having “an off-putting coldness, and an ironic, self-advertising cleverness that proves ultimately repellent” (Daily Telegraph). Internet message boards, such as What’s On Stage, rang with yobbish snorts of “indulgent theatrical wankery” and “pretentious, insulting nonsense”.

These kinds of passionate responses clearly show how central the aesthetics of social realism and naturalism are to British culture. For once, something really is at stake. And, if ever there was an anti-naturalistic play, it’s Attempts on Her Life. With Crimp’s open text, and disregard for the usual literalistic markers of a naturalist play (characters, scenes, dialogue and plot), the piece positively heaves with potential for imaginative stagings. And, in Mitchell’s version, it came across as a phantasmagoria of video effects, fast-paced acting and visual bravura. It is theatrical theatre par excellence. It uses film, but you couldn’t make a film of it.

Bastions of Britishness

Now, it would be easy to dismiss such events, which are happening at the National Theatre — that bastion of Britishness — as somehow irrelevant to the rest of the country’s live performance. Yet the truth is that this flagship has, under the leadership of artistic director Nicholas Hytner, become a trendsetter, a place of innovation rather than conservatism. For example, Hytner associate Tom Morris has championed experimental theatre companies such as Shunt, Kneehigh, Punchdrunk and Improbable, all of whom have been welcomed into the National fold. And the National has contributed immensely to the recent re-emergence of anti-naturalism: look at Mitchell’s own adaptation, Waves (2006). In this transposition of Virginia Woolf’s modernistic novel The Waves Mitchell found a fragmented stage aesthetic that matched the original’s experimental and fragmentary character. Her actors used video to show how reality itself can be constructed and how memory is itself fragmentary. Finally, in a stark illustration of how the National has turned the tables on other so-called cutting-edge theatres, you need only compare two versions of The Seagull. At the National, Mitchell’s version was fast, innovative and shocking; at the Royal Court in 2007, Ian Rickson’s was slow, clichéd and traditional. With its samovars and moody atmosphere, it was a vision of Chekhov that could have been staged at any time during the past thirty years. Mitchell’s production made you sit up; Rickson’s made you yawn.

Hytner has also supported new writing. Of course, it is well know that British new writing for the theatre has been enjoying an unprecedented boom since the mid-1990s. The cult of the new is alive and well. There is now more new writing than at any time before: everywhere you look, both in and outside London, there are new writing festivals, new writing bursaries, new work for kids and new plays on stage. The whole theatre community is rejoicing in the worship of novelty, and the new writing scene is not immune. What is less well known is that there is an aesthetic struggle at the heart of new writing, a tussle between the literalists and the metaphysicals. On the Encore Theatre Magazine website, a posting about the tension between these two great traditions was titled “The Battle Commences”. And the reception of Mitchell’s work is proof that this conflict runs right across all of British theatre.

Landscapes of the Literal

We know all about the literalists. This name refers to the Great British lineage of social realism and naturalism. Its grandparent is George Bernard Shaw and its daddies are John Osborne and Arnold Wesker. It’s a theatre style that Scottish playwright David Greig provocatively calls “English realism”. This new writing genre, which has grown up in subsidised theatres for the past fifty years, shows the nation to itself. What you see on stage is what you get: no more, no less. It voices debates and deals in issues. Its stories are linear and based firmly on a recognisable social context. Its dialogues are convincing and down-to-earth. It is distrustful of metaphor and suspicious of fancy foreign work, which is usually characterised as effete, abstract and humorless. By contrast, English realism is muscular, earthy and wry. Its muscles ripple, but it isn’t gay. With English realism, concludes Greig, “the real world is brought into the theatre and plonked on stage like a familiar old sofa”. Does he have a point? Of course he does. Despite the deluge of the new, most new work is written in this familiar English tradition. And there’s a real failure of theatrical imagination at the heart of the whole literalist endeavour.

Most new plays in Britain are determinedly literal-minded. They are slices of life, soapy dramas for couch potatoes. Whether they are about “me and my mates”, teenage angst or underclass violence, they normally squat on territory that is already known — there’s really little sense of exploration, or experiment, or excitement. The mantra of “write what you know” seems to have banished any imaginative exploration of the tentative or of the partially perceived. Boundaries remain unbreached; fantasy is grounded by the twin ballast of naturalism and social realism. New plays are small in every respect: cast, space and theatrical ambition. This is the theatre landscape that is so familiar to audiences today. And while political theatre has experienced a boom in the wake of 9/11, it too usually returns to the literalist tradition. Think verbatim drama, think docudrama — theatre’s answer to reality tv. As ever, in this genre, often what you see is all there is.

Meet the Metaphysicals

If literalism is familiar, metaphysical theatre is not. But it’s a good label because it calls to mind the tradition of metaphysical poetry, which was championed by TS Eliot in between the wars, and was the subject of a highly influential book of collected poems, edited by Helen Gardner and originally published in 1957, the year after the premiere of Look Back in Anger. In her introduction to these 17th-century poets, Gardner stresses their wit, their conceits and their imagination, and argues that they typically expressed “deep thoughts in common language” and “extraordinary thoughts in ordinary situations”. She also contrasts the “strenuous” and “masculine” style of playwright and poet Ben Jonson with the more elaborate conceits of the true metaphysicals, such as John Donne and Andrew Marvell, who (presumably) were more “effete” and “feminine”. Donne, of course, was a “great frequenter of plays”, and Shakespeare — with his mix of wild imagination, philosophical speculation, onstage ghosts, epic history and domestic realism — can easily be seen as the grand old man of the metaphysical tradition.

But if the metaphysical label doesn’t appeal, maybe another would serve equally well. Playwright Anthony Neilson suggests “psycho-absurdism”, yet absurdism would surely do. (In fact, in summer 2007, there were high-profile London revivals of absurdist plays such as NF Simpson’s A Resounding Tinkle and H Pinter’s The Hothouse.) Or you could call these plays surrealist; or monsterist; or just plain non-naturalistic. I like the idea that these imaginative plays belong to a leftfield tradition, a strand of theatre that runs parallel to the mainstream, but simultaneously questions its hegemonic aesthetics. Anyway, the labels matter a lot less than the work itself. And the fact that it remains a scandal to so many Brits.

The Slump in New Writing

So all is not well in the world of the new. Since 2001, it would be safe to say that English new writing has entered first into a crisis and then into a slump. Nobody says so but, like the absurdist elephant in the front garden, the truth is there for all to see. There simply have been no new writers emerging in the past few years with anything like the talent and impact of Sarah Kane or Mark Ravenhill in the mid-1990s; no new Conor McPhersons from Ireland; no new Martin McDonaghs from south London; and no new David Greigs from Scotland. Of course, there have been plenty of new plays by new wordsmiths, but too few to get excited about. Too few that you remember; too few that people have got het up about. Take Richard Bean, who emerged in 1999 when his play Toast was staged at the Royal Court. Since then, he’s won the prestigious George Devine Award for Under the Whaleback (2003) and the Critics’ Circle Award for Harvest (2005). This prolific writer has had numerous plays staged, but most of them are either work plays — a genre that harks back to the 1960s — or derivative experiments in form. His Honeymoon Suite (2004) put three couples on stage: eighteen-year-olds on their wedding night, forty-three-year-olds on their silver anniversary, and sixty-seven-year-olds married for almost twenty-five years. They were, of course, the same couple, Eddie and Irene, and their lives at different times are shown simultaneously rather than sequentially. This tribute to Caryl Churchill was perfectly entertaining, but also déjà vu.

A couple of younger spirits, such as Dennis Kelly and debbie tucker green, have penned innovative and original dramas, but these are clearly the exceptions rather than the rule. In 2005, green had Stoning Mary staged, a play about the “African” problems of AIDS, Sharia law and child soldiers which she insisted should be played by white actors. In another shorter piece, Generations (2007), she showed a South African family gradually decimated — it was a play about the devastation cause by AIDS without any mention of the disease itself. Similarly, Kelly has been able to articulate some of our current preconceptions without being overtly literal. In the provocatively titled Osama the Hero (Hampstead, 2005) he showed how the War on Terror could seep into the minds of impoverished people on a council estate and in Love and Money (Young Vic, 2007), he described the effects of Britain’s debt culture: in each case, the play’s structure gave an intriguing slant on its subject matter. In Taking Care of Baby (Hampstead, 2007), Kelly also took on verbatim drama with a story which purported to be the real-life case of one Donna McAuliffe, a child killer, told through the testimony of the people involved in the case, but which was actually a satirical fiction. Plays such as these prove that there is some vigour in British new writing: it’s a shame that they are exceptions rather than the rule.

Glowing in the gloom

Still, despite the gloom, it’s hard to abandon all hope. With the arrival of new artistic directors at the main, specialist, new writing theatres, there might be some cause for qualified optimism. For example, Dominic Cooke succeeded Ian Rickson at the Royal Court in 2007. That theatre, once the epitome of forward-looking new writing, has recently begun to look lame. In 2006, its sell-out show was Rock ’N’ Roll by Tom Stoppard, a fine play but hardly innovative or contemporary; in the same year, Tanika Gupta’s Sugar Mummies also sold out, despite the fact that critics saw it as clichéd and soapy. At first glance, Cooke has begun well. His first mainstage show, the National Theatre of Scotland’s revival of Anthony Neilson’s 2004 play, The Wonderful World of Dissocia, is a clear affront to literalism. Showing the mental breakdown of its central character, Lisa, its first half is a mix of Alice in Wonderland with a more contemporary sensibility, and the world of the stage is clearly a reflection of what is happening in Lisa’s troubled mind. And Cooke’s other plans, to stage Crimp’s translation of Ionesco’s Rhinocerous, and to transform the main theatre space to accommodate newcomer Mike Bartlett’s My Child, are both interesting. It is significant, however, that the first show he chose to direct himself was American: Bruce Norris’s The Pain and the Itch.

Other examples of regime change, at the Bush and the Soho, also appear to be encouraging. Lisa Goldman, who began work as the new head of the Soho in 2007, programmed Philip Ridley’s typically imaginative Leaves of Glass as her first play, and then followed this up with two other plays that had their fingers on the pulse of the contemporary: Oladipo Agboluaje’s The Christ of Coldharbour Lane and Hassan Abdulrazzak’s Baghdad Wedding. Okay, so neither was a truly great play, but at least they gave off the smell of current sensibilities. At the Bush, Josie Rourke has taken over from Mike Bradwell, and promises to continue this venue’s tradition of new work, although the track record here has been mainly of literalist slices of life. At the Edinburgh Traverse, new chief Dominic Hill takes over in 2008. Finally, veteran David Lan’s use of his newly refurbished Young Vic theatre has been encouragingly experimental. By giving room to provocative and formally exciting plays such as Kelly’s Love and Money and green’s Generations, in Sacha Wares’s thrilling production, he has shown his support for new writers. In the Big Brecht Fest, he staged the German master’s shorts in new translations by Rory Bremner and the ubiquitous Crimp.

Straightjackets of stiffness

Elsewhere, it is good to note the presence of metaphysical elements in other recent work. As ever, the market leader is Caryl Churchill. Her 2006 play, Drunk Enough To Say I Love You?, was hammered by some of the critics, but its text is an imaginative account of postwar global politics mercifully free of any verbatim claptrap. Her vision of the Anglo-American special relationship as a fractious conversation between a pair of gay lovers is an example of a thrilling shift in perception whose resonance sets off a whole flight of ideas. Mark Ravenhill’s Product (2005) and pool (no water) (2006) both show distinctly Crimpian and Churchillian influences. Playwrights such as Georgia Fitch (Adrenaline… Heart), Kay Adshead (Bones), Simon Stephens (Motortown) and Laura Wade (Breathing Corpses) are at their best when their poetry fractures the form of their plays. But, elsewhere, the straitjacket of literalistic naturalism remains tightly buttoned up, the stiffness of its straps effectively cutting off circulation to the limbs of British theatre nationwide.

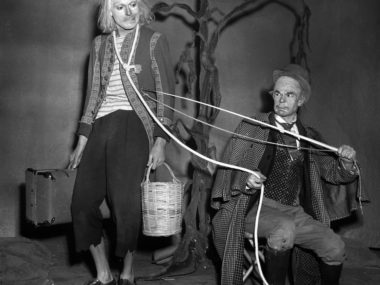

Still, maybe the opposition between literalists and metaphysicals is not the right way of seeing the slump in new writing in England at the moment. Isn’t it a bit stark to confront one tradition so crudely with another? Perhaps the best plays are those that mix naturalistic dialogue with a more leftfield theatrical imagination. If so, perhaps the young British playwrights should look to Ireland for inspiration: Conor McPherson’s The Seafarer (National, 2006) is a play that explores the crisis in masculinity with perfect social realism but, at the same time, it features an onstage Lucifer. Now, that’s pretty metaphysical. Similarly, the Scarecrow in Marina Carr’s Woman and Scarecrow (Royal Court, 2006) was the grim reaper. And it made a breathtaking onstage appearance complete with claws and a devilish-looking tail.

Whether the current grapple between metaphysicals and literalists results in better new plays is as yet uncertain, but it will have done its work if it concentrates minds on that often neglected side of theatre-making: aesthetics. Certainly, British new writing needs a kick in the pants. At the moment, most evenings spent in one of the studio theatres in London are enough to send you back to Chekhov’s Konstantin: “If you ask me,” he says in Crimp’s recent translation, “this theatre of hers is death. When the curtain goes up on yet another adapted novel or some piece of vapid social commentary masquerading as art—when shouting and banging the scenery is mistaken for good acting—when writers think that dialogue means the fluent exchange of platitudes—when I see people churn out the same theatrical clichés time after time after time after time after time, then I want to scream and scream.” Of course, this was originally meant to be a satirical sketch of a hot-headed youth but — after watching yet another piece of British naturalistic social realism — you can see Konstantin’s point. Reality really can be a bore: and if only screaming were enough to change things.

© An earlier version of this article appeared as ‘Reality Sucks: The slump in British new writing’, PAJ: A Journal of Performance and Art 89 (Volume 30, Number 2), May 2008: pp 102-107.