The Skull Beneath the Skin

Tuesday 1st September 2009

In 1920, TS Eliot published ‘Whispers of Immortality’, whose opening lines sum up his response to Jacobean authors such as John Webster: “Webster was much possessed by death/ And saw the skull beneath the skin.” If any contemporary playwright can be said to have drunk from the same cup, that writer would be Philip Ridley. His work, while grounded in the here and now, resonates with a similar sensibility, especially in The Fastest Clock in the Universe, which was first put on at the Hampstead in May 1992.

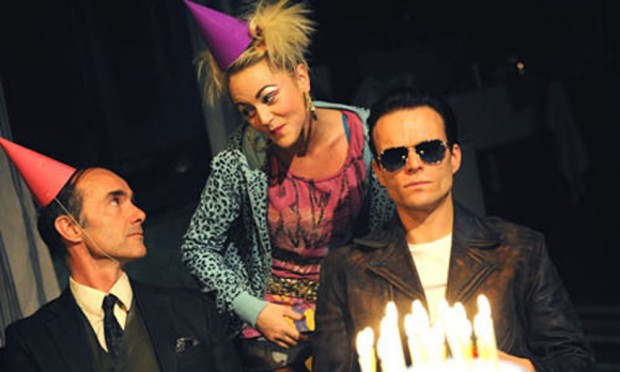

On one level, the play is simple: in an dilapidated room above an abandoned East End factory, thirty-year-old Cougar Glass lives with fiftysomething Captain Tock. Cougar is terrified of aging and whenever his anxieties surface, he decides to throw a birthday party, an excuse to lure some appealing, if under-age, youngster into his seductive clutches. Ridley’s play shows what happens when his prey, the schoolboy Foxtrot Darling, arrives for this celebration — along with his girlfriend, Sherbet Gravel. It’s a birth-day that threatens to become a death-day.

Like any Jacobean tragedy, The Fastest Clock in the Universe is suffused with vivid imagery, anything from the rotting bird under the bridge to the boy who was born without a face. Often these images are described through extended riffs or allegorical short stories. Frequently, the language is allusive. For example, when Cougar says he doesn’t care about having a “gut full of maggots”, you can feel the spirit of Webster twitching behind the wainscoting. Ridley calls such moments of poetic intensity “image arias”, engines of emotion. In his East End, a Gothic sensibility rules okay. Beyond the cosy indoors, you can detect the howling of vampires, cannibal salivations and the fluttering and scurrying of a raft of sinister animals. In this play of highly ritualized encounters and repeated incantations, long shadows from the world of horror seep in and, like so many demonic succubi, make themselves at home.

Again, as in Jacobean tragedy, the play revels in its own extremism, with heightened language and grotesque action. It is also firmly rooted in the human body, in our corporeality. Cougar is clearly obsessed with his body, trying to stop its inevitable aging and its slow loss of youthful freshness. His attempt to keep his body a clean temple of youthfulness, by using sun lamps and hair dyes, is partly a wilful denial of reality, partly a psychological fixation on a moment in his life when the world looked almost praeternaturally bright and hopeful: his first orgasm, on a rooftop, throbbing with electric vibes. It’s the first time he felt truly alive and it’s an experience which he seems destined to seek to repeat, with tragically less and less success. Led by this memory of violent pleasure, he tumbles into sex addiction. He’s forever chasing a buzz. And, as he gets older, his prey gets younger. Ridley’s play is both a social study of narcissism and a mythic account of the fear of nature and of its whispers of mortality.

Cougar is also an embodiment of cool. And cool, as Dick Pountain and David Robins write in their book, Cool Rules, “is a rebellious attitude” but also “self-contained and individualistic”, hiding its defiance “behind a wall of ironic detachment, distancing itself from the source of authority rather than directly confronting it”. With his quiff, sun glasses and hip clothing, his distance and lack of engagement with those around him, Cougar is the cool kid whose psychology has been frozen in time.

Ridley never went to drama school. Instead, he trained as an artist in St Martin’s School of Art, influenced especially by the vivid magic realism of Cecil Collins (1908–89). Ridley brings to the theatre an artist’s sensibility, and an artist’s understanding of animal symbolism. The stuffed birds and tales of mink skinning in The Fastest Clock in the Universe come from the same corner of the imagination as the Damien Hirst’s shark in formaldehyde or his Websterish diamond-encrusted skull. At first, this kinship with the Young British Artists of the 1990s led to Ridley being seriously undervalued by some critics. When The Fastest Clock in the Universe premiered in 1992, with Jude Law as Foxtrot and Con O’Neill as Cougar, the Sunday Times labelled the experience “a sadistic and boring little play which should never have been put on” while the Mail on Sunday dismissed it as “unmitigated bilge”. The Times advised: “A sickbag should be kept in the wings, ready to catch the ugly imagery his characters sporadically throw up.” In those days, the audience outrage was fixated on the abuse of animals, while the fact that a sixteen-year-old schoolboy was about to be seduced by a man almost twice his age excited no comment.

Since his debut in 1991, with the now legendary The Pitchfork Disney, Ridley has established himself as The Poet Prince of East London, penning plays such as Ghost from a Perfect Place and Vincent River (both originally staged at the Hampstead) as well as the iconic gangsterland film, The Krays. But it would be misleading to see Ridley’s work purely as social realism. Like Tennessee Williams’s Deep South, Ridley’s London is just as much a landscape of the imagination: in Mercury Fur, for example, the skies rain hallucinogenic butterflies; in Ghost from a Perfect Place a girl gang makes a religious cult out of a dead mother, and in The Pitchfork Disney a young man wearing a glitter jacket eats live cockroaches for a living. Ridley’s East London is a place of storytelling and myth-making. His plays are labyrinthine journeys into a spellbinding urban territory, at once both magical and menacing, where you might be dazzled by sunlight on razor blades or startled by blood on gold sequins.

In the published text of The Fastest Clock in the Universe, Ridley includes a quotation from French poet Paul Valery: “Your ideas are shocking and your hearts are faint. Your acts of pity and cruelty are absurd, committed casually, as if they were irresistible. Finally, you fear blood more and more. Blood and time.” This sums up perfectly the cathartic nature of Ridley’s play, with its furious chants of “Blood! Blood! Blood!” At the pumping heart of the drama, there is the liquid of life. But also a primal fear of blood. At one point, Cougar is afraid that the Captain will “leak” all over him. This is both an echo of the fear of HIV AIDS and a twisted fear of women, and of their bodies.

Few writers have dug as deep as Ridley has into the dark recesses of our unsettled times. But although he has enjoyed a certain notoriety for the incidental atrocities that spatter his work, The Fastest Clock in the Universe is typical in that it shows how his real forte is the ability to find love and humanity in the unlikeliest places. In the symbiosis between the Captain and Cougar, there’s all the love and hate that any couple might experience. In their power play, there is psychological truth and emotional honesty. But above all, there is the sheer joy of Ridley’s writing, summed up, for me, by Cougar’s lines, somewhere near the start of the play, “We’re all as bad as each other. All hungry little cannibals at our own cannibal party. So fuck the milk of human kindness and welcome to the abattoir!” Well, you can’t say he didn’t warn you!

© An earlier version of this piece appeared as ‘The Skull Beneath the Skin’, programme note for a revival of Philip Ridley’s The Fastest Clock in the Universe, Hampstead Theatre, London (September 2009).