Is God Is, Royal Court

Thursday 16th September 2021

God is a tricky one. Or should that be One? And definitely not a He. So when She says take revenge, then vengeance is definitely not only Hers, but ours too. American playwright Aleshea Harris’s dazzlingly satirical 2018 extravaganza is about two women seeking justice and getting even, and it comes to the Royal Court from New York, trailing shouts of enthusiasm, the prestigious Relentless prize in 2016 and the Obie Award for Playwriting. Unlike many plays about African-Americans this one is refreshingly free from cliché, and this new production does it complete justice.

The set up is gloriously surreal. Two 21-year-old twins, Racine the “rough one”, and Anaia, “trapped in a prison of sweetness”, get a letter from their absent mother, who they haven’t seen for some 18 years and believe to have been killed in the same fire that scarred their young bodies. But she survived, and now calls herself God. When she summons the twins, they obey, promptly leaving their day-care and warehouse jobs. She commands them to seek out their father, known only as Man, and avenge the fire that has hospitalized her in the “Dirty South” for decades and disfigured the bodies of the twins. He is the guilty one and must be punished.

The next moment we are in a road movie, as Racine and Anaia go West and search for their absent and malignant father. As they hit Los Angeles, Racine arms herself with a large rock in a sock (the rhyme here is typical of the joyously jumpy language) and the twins first dispatch Chuck Hall, a suicidal middle-aged lawyer, before arriving at the Man’s home, a yellow house with teak shutters somewhere in the desert. He has two sons, the 16-year-old twins Riley and Scotch, and lives with their mother Angie. Cue blood, lots of blood. The vengeful results of this incursion has echoes of the house of Atreus, mashed up with Webster and Western films, Quentin Tarantino and Martin McDonagh. As the violence escalates, the Hitchcockian murderousness is both hilarious and disturbing.

There’s an electricity in Harris’s writing, a comic crackle and pop that sizzles and screeches, deliberately treating the heaviest of issues — patricide, recurring violence and the effects of trauma — with the lightest of touches. Only at the end are we encouraged to feel anything, and the reason for this profound levity is that we are, it is implied, all creatures of the spectacle now. Having drunk for decades from the liquor of ultra violence, whether on film or on stage, we are hungover and desensitized. Looking through a darksome glass we see the shadows of entertaining viciousness playing across our retinas. Yep, this is our world, our land of the free.

This comic epic reminds us that the fun films we have enjoyed so much for so many decades are really just nasty stories and that what is usually missing is an understanding of trauma. In Harris’s vision, her main characters bear their wounds visibly and her family story pulses with the search for justice. Bad stuff must be avenged. The refreshing thing about the play is its complete scorn for the tropes of black drama. This is a story about African-Americans, and it rings with linguistic virtuosity, but that doesn’t mention police brutality, institutional racism or the Atlantic slave trade. It’s a satirical portrait of suburban America whose thrilling fireworks remind me of Branden Jacobs-Jenkins’s masterpiece, An Octoroon.

Other themes also jostle for your attention: the Man, who has a wild speech about a blackhead as a metaphor for “a blemish you want to get rid of very, very badly”, is a parody of masculinity and comes on stage with all the swagger of a character out of Sergio Leone’s The Good, The Bad and The Ugly. In the “Showdown” scene, the Western duel is represented as a sharp Q&A. Likewise, the escalation of the violence — presented here with beautiful abstraction — suggests a belief that under the surface we are all capable of anything, however bad. Numerous moments of meta-theatre, such as when one of the twins asks, “Was that an awkward pause”, remind us of the artificiality of art, and the music ranges from grinding rap to Puccini.

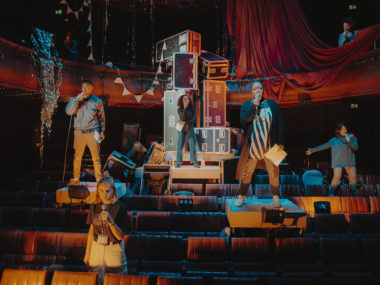

Ola Ince’s superb production brings out the play’s twisted psychology, and its plot swerves, bursts with life on designer Chloe Lamford’s set, which has delightfully humorous props, silly rocks and, by contrast, some fiercely blazing pyrotechnics (thank you Pyro Mark). The fire scars of the female twins are represented as beautiful tattoos, God looks like a refugee from Star Wars, and the male twins are dressed as preppy boys. Tamara Lawrance and Adelayo Adedayo play Racine and Anaia with enormous zest, stressing also the occasional moments of heartbreak. As the other twins, Ernest Kingsley Jnr (making his stage debut as Scotch) and Rudolphe Mdlongwa (Riley) are a wonderful contrast. The rest of the cast — Cecilia Noble (God), Mark Monero (Man) and Ray Emmet Brown (Chuck Hall) — are likewise excellent. Is God Is is a blazing revolt against victimhood and a marvellous account of how the meek could well inherit the world. Yep, this is de luxe American new writing.

This review first appeared on The Arts Desk